An Atlanta based, opinionated commentary on jazz. ("If It doesn't swing, it's not jazz", trumpeter Woody Shaw). I have a news Blog @ News . I have a Culture, Politics and Religion Blog @ Opinion . I have a Technology Blog @ Technology. My Domain is @ Armwood.Com. I have a Law Blog @ Law.

Visit My Jazz Links And Other Websites

Atlanta, GA Weather from Weather Underground

Jackie McLean

John H. Armwood Jazz History Lecture Nashville's Cheekwood Arts Center 1989

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Monday, August 30, 2010

Charlie Haden: A Bassist With A Country Pedigree : NPR

Charlie Haden: A Bassist With A Country Pedigree : NPR

Bassist Charlie Haden is known as a great jazz musician, but his lineage is all country: Growing up, he performed alongside his brothers and sister in the Haden Family Band, a country group led by his parents, Carl and Virginia. The group's music played on radio stations in the South and Midwest, and on the family's country radio show, broadcast on KMA in Shenandoah, Iowa.

In a 2008 interview with Terry Gross, Haden remembers joining his family in their radio broadcasts from a very young age

FT.com / Books / Non-Fiction - Saxophone Colossus

Cover of Saxophone ColossusFT.com / Books / Non-Fiction - Saxophone Colossus

Cover of Saxophone ColossusFT.com / Books / Non-Fiction - Saxophone ColossusSaxophone Colossus: A Portrait of Sonny Rollins, by Bob Blumenthal and John Abbott, Abrams RRP£22.50, 160 pages

These days the great American saxophonist Sonny Rollins will take only those jobs “that put myself, and jazz, in high esteem”. It’s a statement that reflects the distance the New York-born musician has travelled from the circumstances in which he found himself when he recorded the now legendary album Saxophone Colossus in 1956.

Bob Blumenthal and John Abbott’s text-and-photograph collaboration takes that triumphant early album in order to track Rollins’s tumultuous journey from youthful miscreant to venerated statesman – via punishing routines, titanic gigs, heroin addiction and self-imposed exile from performance.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Sonny Rollins wins Miles Davis Award (cbc.ca)

- Jazz Great Sonny Rollins to Receive MacDowell Medal | New Hampshire Public Radio (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

Music Industry Celebrates 40 Years Of Miles Davis' "Brew" - NY1.com

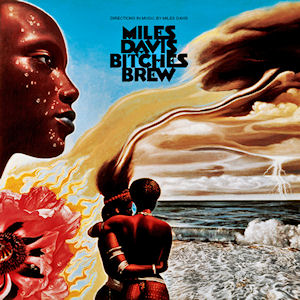

Image via WikipediaMusic Industry Celebrates 40 Years Of Miles Davis' "Brew" - NY1.com

Image via WikipediaMusic Industry Celebrates 40 Years Of Miles Davis' "Brew" - NY1.comA new collectors edition of the groundbreaking jazz fusion album recorded by Miles Davis will be released Tuesday, marking 40 years since its legendary debut. NY1's Stephanie Simon filed the following report.

Forty years later, many are marking the anniversary of Miles Davis' legendary recording "Bitches Brew."

At a recent Celebrate Brooklyn concert in Prospect Park, "Bitches Brew Revisited" saluted the musical pioneer. The band includes some who played with Miles and others who were inspired by him including DJ Logic.

"It feels good to see the old and the young just coming out and supporting and just seeing something unique as well as paying tribute to Miles Davis and the legacy and the music," says DJ Logic.

Drummer Vince Wilburn Junior played for several years with his uncle.

"To me it was like I was a student and he was like the master, the jedi," recalls Wilburn Jr.

Miles Davis wasn't just a musical genius, he was also a brilliant marketer and promoter. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, at a time when rock and roll acts were attracting the big crowds, Davis traded his more traditional look and sound for electric instruments and a rockin' style. The music was called fusion. The album was called "Bitches Brew" and it sold hundreds of thousands of copies. And while some called him a sell out, he was selling out large venues and records, just as he had hoped.

"Miles was a forward thinker so being around him and playing with him, you never knew what to expect. He just had visions in his head and he wanted us to carry it out. He didn't care about what people thought," says Wilburn Jr.

To mark the anniversary, a box set cd and live DVD are being released -- remixed by DJ Logic. A biopic of the restless and experimental musician is also in the works with Herbie Hancock doing the score and actor Don Cheadle tapped to play Miles.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Miles Davis: Bitches Brew 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition | CD review (guardian.co.uk)

- Mad Men, Miles Davis and the Aesthetic of Cool (theroot.com)

- Miles Davis Box Set Out 9/14 (jambase.com)

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Music Review - McCoy Tyner Honors Charlie Parker at Marcus Garvey Park - NYTimes.com

Image via WikipediaMusic Review - McCoy Tyner Honors Charlie Parker at Marcus Garvey Park - NYTimes.com

Image via WikipediaMusic Review - McCoy Tyner Honors Charlie Parker at Marcus Garvey Park - NYTimes.comBy BEN RATLIFF

The permanent amphitheater in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem is a void right now. It’s being rebuilt, band shell and seating. So the Harlem part of the two-day Charlie Parker Jazz Festival, on Saturday afternoon, was moved to a rented stage on a lawn at the northeast corner of the park, next to the farmer’s market, which was still open when the first band started. Later on, a boisterous African drum circle took shape not 100 feet from the stage while McCoy Tyner, though unhappy with the piano’s tuning, boistered back through a solo set.

The permanent amphitheater in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem is a void right now. It’s being rebuilt, band shell and seating. So the Harlem part of the two-day Charlie Parker Jazz Festival, on Saturday afternoon, was moved to a rented stage on a lawn at the northeast corner of the park, next to the farmer’s market, which was still open when the first band started. Later on, a boisterous African drum circle took shape not 100 feet from the stage while McCoy Tyner, though unhappy with the piano’s tuning, boistered back through a solo set.

The free festival has corporate sponsorship but soul prestige; for a Parks Department gig, it books competitively. In the Harlem lineup was Revive Da Live, the changeable collective of young musicians combining jazz and hip-hop; the tenor saxophonist J. D. Allen’s trio; the pianist Jason Moran with his trio, Bandwagon; and Mr. Tyner, one of jazz’s bishops since his time with John Coltrane’s quartet in the early 1960s. (Part 2 of the festival took place Sunday at Tompkins Square Park in the East Village.)

It was a really, really good scene, despite the direct sun pouring down on the audience and the stage. This is where some of the best dreams and desires for jazz in America, neither commercial nor bohemian, come out in a burst: jazz is a cause to defend, a collective memory, a spiritual thing, a Harlem thing. Politicians knew enough to be there: Representative Charles B. Rangel, State Senator Bill Perkins. So did lots of musicians, checking out their friends. Older men and women with hats and picnic baskets, returnees every year, all looking as if they owned their patch of park, asking who brought the corkscrew and what’s the name of that song. A festival operative standing in front of the stage, hollering praise during the music like a running commentary.

Mr. Tyner, now 71, wasn’t doing that much with the idea of a solo-piano concert; if there had been a band behind him, it might have sounded much the same. Still making his left-hand chords boom like kettle drums, he played some of his own songs, Coltrane’s “Mr. P.C.,” and a rubato “I Should Care,” weighed down with ornament. He kept his foot on the sustain pedal for almost the entire 40 minutes; nearly the only exceptions came when he stole away from the song to splash the keyboard abstractly. It was a strange set, monolithic but distracted. He ended by apologizing for the weather’s impact on the piano, as yet another politician escorted him offstage: his younger brother, Jarvis Tyner, executive vice chairman of the Communist Party USA.

Revive Da Live, an octet with a rapper and D.J., Raydar Ellis, brought arrangements of Parker tunes and solos. The modern frames were cool sometimes, but it was individual performances, especially from Marc Cary on electric piano and Marcus Strickland on tenor saxophone, that put it over. And Jason Moran’s Bandwagon played a loose and typically meta-historical set that went heavy on sound samples and recontextualized quotations. The band played hard over recordings of Eddie Jefferson’s vocalese version of “Body and Soul” and Billie Holiday’s “Big Stuff.”

But J. D. Allen made the most of the day. His trio doesn’t try to be comprehensive or world-spanning or express the new jazz pedagogy; it performs strong, short melodies and rhythms that develop a little and then end. Its music is bracing and easy to follow, looking toward the language of free jazz but staying close to the themes’ guideposts, and never letting the rhythm get baggy.

Something really good has happened to this trio over the last five years. First it secured its sound on the bandstand. (One of the quirks of that sound is that the bassist, Gregg August, roams furthest from the groove, while the leader and the drummer stay in lockstep; here he was boosted good and loud in the mix.) Then it set to work on its performance ritual, its relationship with audiences.

On Saturday the band got its pacing exactly right and didn’t let the crowd rest. It kept coming with new melodies; sometimes it joined pieces together, and sometimes it came to a complete stop, but only for about a second and a half. It changed tempo and mood, not much but just enough. And it got the most concentrated response from the audience, even from the older folks.

Daily Herald | Chicago Jazz Festival turning 32 and it's free

Image via WikipediaDaily Herald | Chicago Jazz Festival turning 32 and it's free

Image via WikipediaDaily Herald | Chicago Jazz Festival turning 32 and it's freeThe city's longest running lakefront music festival, the Chicago Jazz Festival turns 32 and this year's performers at the free fest include Nicole Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, Brad Mehldau, Ramsey Lewis, Brian Blade and the Fellowship Band, Rene Marie, The Either/Orchestra and Kurt Elling. Venues include Grant Park, the Chicago Cultural Center and Millennium Park. Bring the kids for their own activity area.

Noon-5 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 2; noon-9:30 p.m., Friday, Sept. 3-Sunday, Sept. 5. Millennium Park, Jay Pritzker Pavilion, North Michigan Avenue and East Randolph Street; Chicago Cultural Center, 77 E. Randolph; and Grant Park Jackson Boulevard and Columbus Drive, Riff on chicagojazzfestival.us or call (312) 744-3315.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Nicole Mitchell stars at the upcoming Chicago Jazz Festival (avantmusicnews.com)

- 32nd Annual Chicago Jazz Festival Lineup (avantmusicnews.com)

Marsalis, lending sound to a silent | Philadelphia Inquirer | 08/29/2010

Image by Getty Images via @daylifeMarsalis, lending sound to a silent | Philadelphia Inquirer | 08/29/2010

Image by Getty Images via @daylifeMarsalis, lending sound to a silent | Philadelphia Inquirer | 08/29/2010On Tuesday, the Keswick Theatre in Glenside hosts an event that, at first glance, might seem like a mismatch, even bizarre.

Jazz trumpet master Wynton Marsalis and a 10-piece ensemble will be accompanying - a silent film.

Yet that silent film is new, not old, and so are events like this, at which musical masters play live to accompany silent movies.

The film in question is Louis, directed by Dan Pritzker and shot by Oscar-winning cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Close Encounters of the Third Kind). It's less of a biopic than a riff on the life of Louis Armstrong.

Marsalis' group, featuring Victor Goines, Ted Nash, and other stalwarts of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, will play original pieces along with classic works by Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington. Philadelphia is the last stop on a tour that includes Chicago, Detroit, Washington, and New York's Apollo Theater.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Louis: A Silent FIlm (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- A Silent Musical (nytimes.com)

- Wynton Marsalis Scores Silent Film 'Louis,' Plus Five Great Jazz Film Scores (huffingtonpost.com)

Friday, August 27, 2010

Jazz, Very Much Alive, in Paris - NYTimes.com

Jazz, Very Much Alive, in Paris - NYTimes.com

No one embraces jazz like the French. They first fell under its spell in the 1920s, when American artists like Josephine Baker and Sidney Bechet found refuge in their country, disillusioned by the racial situation in the United States. Still among jazz’s biggest supporters, the French hold terrific festivals, like Jazz à la Villette, which runs from Aug. 31 to Sept. 12 in beautiful Parc de la Villette and other venues around Paris.

The festival, which actually ranges beyond jazz to include hip-hop, soul and Afro-beat, pairs seemingly dissimilar artists to give audiences rare and unusual musical experiences. “We try to show the links between jazz and the other kinds of music,” said Vincent Anglade, the festival director. “We want to abolish the frontiers and avoid the labels. We look for a good balance between European and U.S. artists, between young talent and great legends and between straight-ahead jazz and crossover.”

Opening night, for instance, brings together the avant-garde guitarist Marc Ribot and the rapper and bassist Meshell Ndegecello; the Afro-beat drummer Tony Allen, the Finnish saxophonist Jimi Tenor and the African trio Kabu Kabu collaborate on Sept. 1. Calling themselves the Now He Sings Now He Sobs Trio, the jazz superstars Chick Corea and Roy Haynes join Miroslav Vitous, a bassist formerly of the band Weather Report, in a performance on Sept. 2. And, in one of the most anticipated concerts, on Sept. 7, the renowned Cuban pianist Chucho Valdes joins the saxophonist Archie Shepp in the Afro-Cuban Project.

“It’s great to be asked who you want to play with,” Mr. Shepp said. “I don’t know another festival that does that. And then, to get the musician of your choice — in my case, wonderful Chucho, that’s incredible. I started out with a Puerto Rican ensemble and I’ve always had a fondness for Latin music, it’s so close to the feeling of dance. I’m very excited about getting back into it with him. Especially in La Villette. The audience is so responsive.”

For more information, call 33-1-44-84-44-84; for tickets, visit www.ticketnet.fr; prices range from 10 to 35 euros, about $12.50 to $43.50

Related articles by Zemanta

- Don Byron: Jazz musician puts his faith in gospel - thestar.com (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

BBC News - World News America - Jazz to overcome tragedy of Katrina

BBC News - World News America - Jazz to overcome tragedy of Katrina

Terence Blanchard, one of the world's leading trumpet players, fled Louisiana during Hurricane Katrina.

Several months later he was inspired to record A Tale of God's Will, an album about the city's post-hurricane struggles.

In this first person account, he explains how music will help Louisiana's citizens to move past the tragedy.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Spike Lee Screens New Hurricane Katrina Film (theroot.com)

- Chron.com: 5 years after Katrina, TV, film revisiting the tragedy (chron.com)

- The Post-Katrina Demographic Shift: Older, Whiter, Wealthier (fastcompany.com)

Sunday, August 22, 2010

First Listen: Danilo Pérez, 'Providencia' : NPR

First Listen: Danilo Pérez, 'Providencia' : NPR

The members of the Wayne Shorter Quartet call their pianist Danilo Pérez "the galactic ambassador," and there's some truth in the nickname. His mission has a certain spatial quality of vastness: For a decade, he has been the cultural ambassador for his native Panama, where he runs the Fundación Danilo Pérez, and every January, he serves as a UNICEF World Ambassador at the Panama Jazz Festival, an event he created. At this year's opening ceremony, the first lady of Panama awarded Pérez the nation's highest honor for the arts, the Orden Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. That same night, Boston's Berklee College of Music named him the artistic director of the newly created Berklee Global Jazz Institute.

Providencia, Danilo Pérez's debut on Mack Avenue Records, stuffs a lot of directive into 50 minutes of music. Pérez and his eight-year-old trio, with bassist Ben Street and drummer Adam Cruz, are the pivot point. In "Historia de un Amor," a staple from Panamanian composer Carlos Eleta Almaran, Pérez and company move into a harmonic evocation of the song's central idea — the suffering of a love forever gone. There's also the quiet reclamation of "Irremediablemente Solo" by Avelino Muñoz, a man better known as an organ salesman in Puerto Rico than as a great bolero writer.

As the Detroit jazz fest's artist-in-residence, pianist Mulgrew Miller celebrates the icons who shaped him | freep.com | Detroit Free Press

As the Detroit jazz fest's artist-in-residence, pianist Mulgrew Miller celebrates the icons who shaped him | freep.com | Detroit Free Press

The apprentice system was once the lifeblood of jazz. Gifted young musicians moved to a major city like New York, signed on with one of dozens of working bands and assimilated the subtleties of the tradition on the bandstand.

But that system has been running on fumes since the 1980s. Economic and cultural changes decimated clubs, reshaped the recording industry and moved jazz further to the margins of contemporary culture. Few opportunities remain for young musicians to crisscross the country with name bands or work steady local gigs with veterans. Meanwhile, former apprentices who paid their dues struggle for their day in the sun.

Pianist Mulgrew Miller, artist-in-residence of the 2010 Detroit International Jazz Festival, just made it under the wire. Miller joined the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1977 at age 21 and for the next 17 years worked steadily with some of the most imposing leaders in jazz -- drummers Art Blakey and Tony Williams, Detroit-bred singer Betty Carter and trumpeter Woody Shaw. At 55, he's one of the most respected and recorded musicians of his generation, a standard bearer for mainstream values of swing, melodic improvising, harmonic sophistication, polished technique and a tall drink of the blues.

He is, in other words, a flame keeper.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Detroit Jazz Fest expands interactive presence | detnews.com | The Detroit News (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Duke Ellington: His Life Story, Part Two | Special English | Learning English The Voice Of America

Duke Ellington: His Life Story, Part Two | Special English | Learning English

Related articles by Zemanta

- Duke Ellington's America (3quarksdaily.com)

- Joya Sherrill, Who Sang With Ellington and Goodman, Is Dead at 85 (nytimes.com)

- Book Review - Duke Ellington's America - By Harvey G. Cohen (nytimes.com)

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Steve Coleman: 'Harvesting' Funky, Brainy Jazz : NPR

Steve Coleman: 'Harvesting' Funky, Brainy Jazz : NPR

As a composer, Steve Coleman has been heavily influenced by James Brown's funk. You wouldn't mistake Coleman's band Five Elements for the J.B.'s, but like the Godfather of Soul, he goes in for fast, jittery beats. On Coleman's new album, Harvesting Semblances and Affinities, Five Elements is powered by a rhythm duo who sync up in a few bands: bassist Thomas Morgan and drum phenom Tyshawn Sorey.

Steve Coleman has always connected with singers. Coming up in the 1980s, he worked with the veteran Abbey Lincoln and fellow newcomer Cassandra Wilson. Jen Shyu's role is slippery here. She's not quite out front and not quite fully aligned with the sextet's three horns. Her main feature is the one non-original tune, Coleman's setting of a choral work by Danish composer Per Nørgård. He's an influence on Coleman's own arcane ways of developing material — like dipping into the so-called undertone series, which is basically the natural overtone series turned upside down. Don't ask me to explain it, but you can find out more about the undertone series here and how Coleman uses it here.

If Steve Coleman's music sounds a little chilly sometimes, it's because he's more interested in compositional logics than setting a mood. That's okay; there's room for all kinds of approaches. That adapted choral music prompts us to see Coleman as a composer of modern art songs. His pieces often revolve around looping phrases or recurring patterns that overlap or seep into each other. It's the West African drum-choir principle: Wheels within wheels can keep rolling indefinitely.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Steve Coleman and Five Elements: Harvesting Semblances and Affinities | CD review (guardian.co.uk)

- Steve Coleman and Five Elements: Harvesting Semblances and Affinities (avantmusicnews.com)

Don Byron: Jazz musician puts his faith in gospel - thestar.com

Don Byron: Jazz musician puts his faith in gospel - thestar.com

American clarinetist Don Byron didn’t hesitate when the Markham Jazz Festival’s new artistic director asked him to be the event’s first-ever artist-in-residence.

“He is one of my dearest friends; any excuse that I have to be around him, I’ll take it,” said Byron of the overture from Toronto composer/guitarist Michael Occhipinti, curator of the 13th annual program of free and ticketed concerts that runs Friday to Sunday.

Each day of the festival will find Byron performing in a different configuration: at Friday’s gala with bassist Cameron Brown’s Hear & Now quartet; helming his own New Gospel Quintet on Saturday; and Sunday with Occhipinti’s new band Triodes.

Longtime fans will be keen on the Canadian premiere of Byron’s year-old gospel project, which primarily plays the music of Chicago composer Thomas A. Dorsey who was known as “the father of gospel music.”

Related articles by Zemanta

- Jazz Great Sonny Rollins to Receive MacDowell Medal | New Hampshire Public Radio (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- Markham Jazz Festival: A little fest with big ideas (theglobeandmail.com)

Fresh Air Remembers Jazz Singer Abbey Lincoln | WBUR & NPR

Fresh Air Remembers Jazz Singer Abbey Lincoln | WBUR & NPR

Fresh Air Remembers Jazz Singer Abbey Lincoln

Portions of this interview were originally broadcast on March 25, 1986, and June 16, 1996.

Abbey Lincoln, the jazz singer who transformed herself from a supper-club singer into a powerful voice in the civil-rights movement, died Saturday. She was 80.

Lincoln started her career singing in nightclubs and dinner theaters in the early 1950s -- first in Honolulu and later in Chicago and New York. While performing at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village, she met drummer and bebop innovator Max Roach, who introduced her to modern jazz, and to a performing style influenced by the new black consciousness.

After Roach and Lincoln married in 1962, they recorded a series of albums together, where Lincoln was backed by jazz legends such as Sonny Rollins and Eric Dolphy. Her songs became less pop-based and began to reflect her growing involvement in the civil rights and black pride movements.

Lincoln sang the vocal tracks on Roach's album We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, the now-famous civil-rights document. While recording throughout the '60s, she also took to Hollywood, starring in 1964's Nothing but a Man, about a young black couple in the South, and then co-starring in the 1968 romantic comedy For Love of Ivy opposite Sidney Poitier.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Abbey Lincoln, Jazz Singer and Writer, Dies at 80 - Obituary (Obit) - NYTimes.com (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

NorthJersey.com: Music educators pass the jazz torch

Image via WikipediaNorthJersey.com: Music educators pass the jazz torch

Image via WikipediaNorthJersey.com: Music educators pass the jazz torchChristian McBride, the multi Grammy award-winning bassist, likes to say that jazz is a lifetime journey of learning and discovery.

For the past two weeks, dozens of young people hopped on that road, and they did it alongside some very impressive musical company. More than 75 youngsters spent their late August summer vacation practicing their instruments, learning new compositional and improvisational techniques, and sitting in on workshops featuring some of the top jazz working professionals who make their homes in Montclair and nearby towns. It was all part of the Jazz House Kids (JHK) Summer Camp and it unfolded every day beginning on Aug. 9, in The Salvation Army Montclair Citadel on Trinity Place.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Jazz Great Sonny Rollins to Receive MacDowell Medal | New Hampshire Public Radio (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- Jazz Musician Billy Taylor Turns Eighty-Nine 7/24 2010/07/21 (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- SentinelSource.com |COOL JAZZ (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Music - Coleman Hawkins Outplays Himself in Savory Collection - NYTimes.com

Music - Coleman Hawkins Outplays Himself in Savory Collection - NYTimes.com

There isn’t just one recording angel, or even a select few; there are thousands, maybe millions. Each rediscovery of old sound recordings comes to us through a different human filter: a person with a specific job, with specific tastes or aspirations.

And yet some recordings seem as if they were meant to survive, as if they were too good not to, no matter what the circumstances of their transmission through the ages, their purpose and their ownership and their custodians. In other words, sometimes a recording feels like art history, not just social history.

Among the recently discovered jazz recordings from the late 1930s into 1940 made by William Savory, an audio engineer, at least a few rise to this level. There are nearly 1,000 acetate and metal discs in the Savory Collection. Ninety percent of them haven’t been digitized or even played, and of the 10 percent remaining, I’ve heard only about a dozen complete tracks. I’m in no position to assess the whole thing. (Nobody is yet in any position to assess when, how or what portion of the recordings can be commercially released.) But all that I’ve heard are special. And at least one is amazing: a live recording of “Body and Soul” by Coleman Hawkins from May 1940.

Mr. Savory, who died in 2004, worked in New York during the 1930s as an engineer for a transcription service: the kind of outfit with access to live radio broadcasts from around the country, and the ability to make disc copies of the broadcasts for whoever needed them. Evidently he brought home copies of what he liked as a fan, what he thought important or what had sentimental value, for here was a guy who befriended jazz musicians. That’s it: no master plan, no urge toward comprehensiveness.

Looking through the names on the discs — cataloged by Loren Schoenberg, the jazz scholar and executive director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, which recently bought the collection from Mr. Savory’s family — I saw a whole lot of Benny Goodman, because Mr. Savory loved Goodman’s music and came to know him. (He eventually married one of Goodman’s singers, Helen Ward, after she had left the band.) There’s a lot of Teddy Wilson, probably for similar reasons. There are recordings of now obscure swing-band saxophonists: Tony Zimmers, Stewie McKay. There’s some Billie Holiday, some Cab Calloway, some Mildred Bailey, a tiny bit of Louis Armstrong and John Kirby, and some extravagantly good jam-session Lester Young. And Coleman Hawkins.

When Hawkins came back from a five-year European stay in the summer of 1939, the disposition of his music had changed. He had been playing a different role with audiences; he had become a star who blotted out the importance of his sidemen. In England and Switzerland and the Netherlands, audiences treated him with deference, as an exotic and a master soloist.

After his return, the record producer John Hammond remarked with dismay that he had become a “rhapsodist,” but that was no easy accomplishment. The studio recording of “Body and Soul,” from October 1939, is an event, an actorly tour de force in three minutes, a continuous solo after a loose statement of theme; its equivalent in another form of music might be Jimi Hendrix’s “Star-Spangled Banner.” (Hawkins once said that Thelonious Monk, incredulous and envious that the record had become a hit, told him, “There’s no melody in there; what are they listening to?”)

It was Hawkins’s most famous song, and he recorded it many times again: the complete list includes stage versions from 1949 at Carnegie Hall and in Lausanne, Switzerland; studio revisits in 1956 with an orchestra and in 1958 with the clarinetist Tony Scott; and from 1944 a more abstracted version of the song — with even less of a melody — copyrighted as “Rainbow Mist.” What we haven’t had is an example of how he played it in clubs right after the record came out. Wouldn’t that be nice? Wouldn’t that be helpful to the historical record?

That’s what Mr. Savory kept for us. This “Body and Soul,” from May 1940, comes from a gig broadcast from the Fiesta Danceteria, then a new joint in Times Square, where you could buy cafeteria food as a cover charge and dance to music free. According to “The Song of the Hawk,” John Chilton’s biography of Hawkins, the engagement went badly. The owners asked him to play stock arrangements of pop songs until the late set, and even then asked Hawkins to quiet down his brass players. Hawkins quit after a week.

But you wouldn’t suspect any of that. The Savory version, clear enough to indicate the breadth of his sound, is three minutes and two choruses longer than the studio recording seven months earlier, at a marginally faster tempo, and just as psychologically intense. Presumably many listeners knew the whole recorded improvisation by heart, but here he rarely refers to it. The performance takes its time, as Hawkins develops his improvisation alone over bass and drums, with gathering abstraction from the tune.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Jazz treasure trove to be made public (guardian.co.uk)

- National Jazz Museum Acquires Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

- National Jazz Museum in Harlem Acquires New Recordings 2010/08/16 (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

Jazz treasure trove to be made public | Music | guardian.co.uk

Jazz treasure trove to be made public | Music | guardian.co.uk

Jazz treasure trove to be made public

Savory Collection, featuring rare live sets by Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday and Coleman Hawkins, to go on display at US National Jazz Museum

Sean Michaels

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 18 August 2010 10.15 BST

larger | smaller

In full Swing ... Louis Armstrong in the 1930s. Photograph: AP

Some of the most sought-after recordings in early jazz will soon be available to the public – at least if you're willing to travel to Harlem. The Savory Collection, including rare live sets by Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Coleman Hawkins and many more, is to be displayed at the US National Jazz Museum, and with it, some of the only 1930s jazz recordings more than a few minutes long.

During the late 30s, audio engineer William Savory recorded nearly 1,000 discs of radio broadcasts, capturing an unparalleled slice of the swing era. Although there are already lots of jazz recordings from that period, most are no more than three minutes long: the limitations of 10in 78-rpm shellac discs made longer recordings impossible. As the New York Times reports, Savory's collection is different. With aluminium or acetate discs 12- or 16in wide, sometimes recorded at 33 1/3 rpm, he was able to capture longer performances "in their entirety", according to the paper, "including jam sessions at which musicians could stretch out and play extended solos that tested their creative mettle".

The audio quality is also high. Savory was "a technical genius", explained the museum's executive director, Loren Schoenberg. "You hear some of this stuff and you say, 'This can't be 70 years old.'" The collection includes unreleased music by Count Basie, Lester Young and Benny Goodman; the only known recordings from the world's first outdoor jazz festival, in 1938; a six-minute version of Body and Soul, performed by Coleman Hawkins; and Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit, accompanied by piano, less than a month after the original recording was released. "You have the most inane scripted introduction ever," Schoenberg said, "but then Billie comes in, and she drives a stake right through your heart."

Related articles by Zemanta

- National Jazz Museum in Harlem Acquires New Recordings 2010/08/16 (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- The Savory Collection Likely to Hold More Surprises for Jazz Fans (artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com)

- Music: Coleman Hawkins Outplays Himself in Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

- Jazz Singer Abbey Lincoln Dead at 80 (theroot.com)

- National Jazz Museum Acquires Savory Collection (nytimes.com)

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

SentinelSource.com |COOL JAZZ

SentinelSource.com |COOL JAZZ

Composer, musician Sonny Rollins honored

By Casey Farrar

Sentinel Staff

Published: Monday, August 16, 2010

PETERBOROUGH — An aura of cool hung in the air Sunday as The MacDowell Colony honored jazz composer and tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins during its annual Medal Day celebration.

Rollins, 79, was the 51st artist to be awarded the medal and the first jazz composer to be recognized by the colony for “an outstanding contribution to the arts,” according to the colony’s website.

Rollins told an audience of about 1,600 people he was humbled by the honor.

“Every time people tell me I help make their lives a little better, why then I realize that I’ve come full circle,” he said. “I love (music) for myself, but if I can give something to somebody else then that’s perfect.”

The MacDowell Colony was founded in 1907 by composer Edward MacDowell and his wife, Marian. Each year, artists are selected from all over the country and world to stay for free at one of the colony’s 32 studios as an artist-in-residence.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Sonny Rollins wins Miles Davis Award (cbc.ca)

- Jazz Great Sonny Rollins to Receive MacDowell Medal | New Hampshire Public Radio (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

National Jazz Museum in Harlem Acquires New Recordings 2010/08/16

National Jazz Museum in Harlem Acquires New Recordings 2010/08/16

The National Jazz Museum in Harlem (NJMH) today announced the acquisition of a historic collection of never-before-heard recordings, including live performances of great American Jazz icons from 1935-1941. The collection of 975 aluminum and vinyl discs, over 100 hours of material, was created by William Savory, a recording engineer and Harvard-educated physicist. Savory worked as at a radio transcription service in New York between 1935 and 1941 and used the equipment his job afforded him to record hundreds of hours of material directly off the radio.

The collection includes live performances by Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Lionel Hampton, Fats Waller, Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman, and more, as well as classical broadcasts including Toscanini, Ormandy, and Kristen Flagstad. The quality of the discs is extraordinary for the time, as most jazz enthusiasts in the 1930s did not have the access to professional equipment that Savory enjoyed.

The National Jazz Museum in Harlem's Executive Director Loren Schoenberg discovered the collection after a 24 year cultivation that started with his meeting William Savory in 1980. Savory died in 2004 and Schoenberg acquired the discs in April, 2010 for the museum through Savory's heir, Eugene Desavouret, of Malta, Illinois.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Jazz @ the Dwyer: A Big Band Swing and Dance Party (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- Harlem Week at Gracie Mansion (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- City seeks developer for Harlem jazz museum (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

- NYC seeks developer for jazz museum in Harlem (dailycaller.com)

Monday, August 16, 2010

First Listen: The Marsalis Family, 'Music Redeems' : NPR

First Listen: The Marsalis Family, 'Music Redeems' : NPR

Today's first family of jazz, the Marsalises don't often get together, at least on stage. But when the Duke Ellington Jazz Festival in Washington, D.C. (now the DC Jazz Festival), gave its 2009 lifetime achievement award to family father Ellis Marsalis — a great pianist and legendary educator — all four of his music-playing sons (Wynton, Branford, Delfeayo and Jason) joined him on stage. Ellis Marsalis III also recited an original poem for his father, frequent collaborators Herlin Riley and Eric Revis stepped in, Dr. Billy Taylor joined in the fun, and family friend Harry Connick Jr. took a few guest spots, too.

Marsalis Music, the record label founded by Branford, recorded the show. Now, it's releasing part of the concert as Music Redeems. But this isn't a money grab: All proceeds from sales are going to the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music, the practice, teaching, recording and performing space currently under construction as the heart of the New Orleans Habitat Musicians' Village. (Following Hurricane Katrina, Connick and Branford Marsalis initiated the construction of a community for New Orleans musicians, many of whom lived in substandard housing even before Katrina.)

The music captured here feels casual in the best way. There's the deft reading of "Donna Lee," with a muted Wynton bebop-soloing away and Jason whistling the rapid-fire melody. Or the joyous back-and-forth New Orleans feel of "At the House in Da Pocket" and "The 2nd Line," the blues tunes which close out the album. Or Ellis Marsalis' solo piece "After," or his duet with Harry Connick Jr. on "Sweet Georgia Brown," or the charming story Connick tells about taking piano lessons in the Marsalis household as a child. It's as if the family and friends were gathering for a jam session on stage, and amazing each other at every turn.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Marsalis family earns U.S. jazz honour (cbc.ca)

- At Newport, jazz ranging to the ends of its scale - The Boston Globe (armwoodjazz.blogspot.com)

- Marsalis Family Chosen for 2011 Jazz Masters Award (abcnews.go.com)

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Abbey Lincoln, Jazz Singer and Writer, Dies at 80 - Obituary (Obit) - NYTimes.com

Cover of Abbey Sings AbbeyAbbey Lincoln, Jazz Singer and Writer, Dies at 80 - Obituary (Obit) - NYTimes.com

Cover of Abbey Sings AbbeyAbbey Lincoln, Jazz Singer and Writer, Dies at 80 - Obituary (Obit) - NYTimes.comAbbey Lincoln, a singer whose dramatic vocal command and tersely poetic songs made her a singular figure in jazz, died on Saturday in Manhattan. She was 80 and lived on the Upper West Side.

Her death was announced by her brother David Wooldridge.

Ms. Lincoln’s career encompassed outspoken civil rights advocacy in the 1960s and fearless introspection in more recent years, and for a time in the 1960s she acted in films with Sidney Poitier.

Long recognized as one of jazz’s most arresting and uncompromising singers, Ms. Lincoln gained similar stature as a songwriter only over the last two decades. Her songs, rich in metaphor and philosophical reflection, provide the substance of “Abbey Sings Abbey,” an album released on Verve in 2007. As a body of work, the songs formed the basis of a three-concert retrospective presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2002.

Her singing style was unique, a combined result of bold projection and expressive restraint. Because of her ability to inhabit the emotional dimensions of a song, she was often likened to Billie Holiday, her chief influence. But Ms. Lincoln had a deeper register and a darker tone, and her way with phrasing was more declarative.

“Her utter individuality and intensely passionate delivery can leave an audience breathless with the tension of real drama,” Peter Watrous wrote in The New York Times in 1989. “A slight, curling phrase is laden with significance, and the tone of her voice can signify hidden welts of emotion.”

She had a profound influence on other jazz vocalists, not only as a singer and composer but also as a role model. “I learned a lot about taking a different path from Abbey,” the singer Cassandra Wilson said. “Investing your lyrics with what your life is about in the moment.”

Ms. Lincoln was born Anna Marie Wooldridge in Chicago on Aug. 6, 1930, the 10th of 12 children, and raised in rural Michigan. In the early 1950s, she headed west in search of a singing career, spending two years as a nightclub attraction in Honolulu, where she met Ms. Holiday and Louis Armstrong. She then moved to Los Angeles, where she encountered the accomplished lyricist Bob Russell.

It was at the suggestion of Mr. Russell, who had become her manager, that she took the name Abbey Lincoln, a symbolic conjoining of Westminster Abbey and Abraham Lincoln. In 1956, she made her first album, “Affair ... a Story of a Girl in Love” (Liberty), and appeared in her first film, the Jayne Mansfield vehicle “The Girl Can’t Help It.” Her image in both cases was decidedly glamorous: On the album cover she was depicted in a décolleté gown, and in the movie she sported a dress once worn by Marilyn Monroe.

For her second album, “That’s Him,” released on the Riverside label in 1957, Ms. Lincoln kept the seductive pose but worked convincingly with a modern jazz ensemble that included the tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins and the drummer Max Roach. In short order she came under the influence of Mr. Roach, a bebop pioneer with an ardent interest in progressive causes. As she later recalled, she put the Monroe dress in an incinerator and followed his lead.

The most visible manifestation of their partnership was “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite,” issued on the Candid label in 1960, with Ms. Lincoln belting Oscar Brown Jr.’s lyrics. Now hailed as an early masterwork of the civil rights movement, the album radicalized Ms. Lincoln’s reputation. One movement had her moaning in sorrow, and then hollering and shrieking in anguish — a stark evocation of struggle. A year later, after Ms. Lincoln sang her own lyrics to a song called “Retribution,” her stance prompted one prominent reviewer to deride her in print as a “professional Negro.”

Ms. Lincoln, who married Mr. Roach in 1962, was for a while more active as an actress than a singer. She starred in the films “Nothing but a Man,” in 1964, and “For Love of Ivy,” opposite Sidney Poitier, in 1968. But with the exception of “Straight Ahead” (Candid), on which “Retribution” appeared, she released no albums in the 1960s. And after her divorce from Mr. Roach in 1970, she took an apartment above a garage in Los Angeles and withdrew from the spotlight for a time. She never remarried.

In addition to Mr. Wooldridge, Ms. Lincoln is survived by another brother, Kenneth Wooldridge, and a sister, Juanita Baker.

During a visit to Africa in 1972, Ms. Lincoln received two honorary appellations from political officials: Moseka, in Zaire, and Aminata, in Guinea. (Moseka would occasionally serve as her surname.) She began to consider her calling as a storyteller and focused on writing songs.

Moving back to New York in the 1980s, Ms. Lincoln resumed performing, eventually attracting the attention of Jean-Philippe Allard, a producer and executive with PolyGram France. Ms. Lincoln’s first effort for what is now the Verve Music Group, “The World Is Falling Down” (1990), was a commercial and critical success.

Eight more albums followed in a similar vein, each produced by Mr. Allard and enlisting top-shelf jazz musicians like the tenor saxophonist Stan Getz and the vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. In addition to elegant originals like “Throw It Away” and “When I’m Called Home,” the albums featured Ms. Lincoln’s striking interpretations of material ranging from songbook standards to Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

For “Abbey Sings Abbey” Ms. Lincoln revisited her own songbook exclusively, performing in an acoustic roots-music setting that emphasized her affinities with singer-songwriters like Mr. Dylan. Overseen by Mr. Allard and the American producer-engineer Jay Newland, the album boiled each song to its essence and found Ms. Lincoln in weathered voice but superlative form.

When the album was released in May 2007, Ms. Lincoln was recovering from open-heart surgery. In her Upper West Side apartment, surrounded by her own paintings and drawings, she reflected on her life, often quoting from her own song lyrics. After she recited a long passage from “The World Is Falling Down,” one of her more prominent later songs, her eyes flashed with pride. “I don’t know why anybody would give that up,” she said. “I wouldn’t. Makes my life worthwhile.”

_____________________________________

I had the great pleasure of producing a concert featuring Abbey Lincoln in Atlanta, Georgia in 1991.

John H. Armwood

Related articles by Zemanta

- Abbey Lincoln: Abbey Is Blue/It's Magic | CD review (guardian.co.uk)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)