An Atlanta based, opinionated commentary on jazz. ("If It doesn't swing, it's not jazz", trumpeter Woody Shaw). I have a news Blog @ News . I have a Culture, Politics and Religion Blog @ Opinion . I have a Technology Blog @ Technology. My Domain is @ Armwood.Com. I have a Law Blog @ Law.

Visit My Jazz Links And Other Websites

Atlanta, GA Weather from Weather Underground

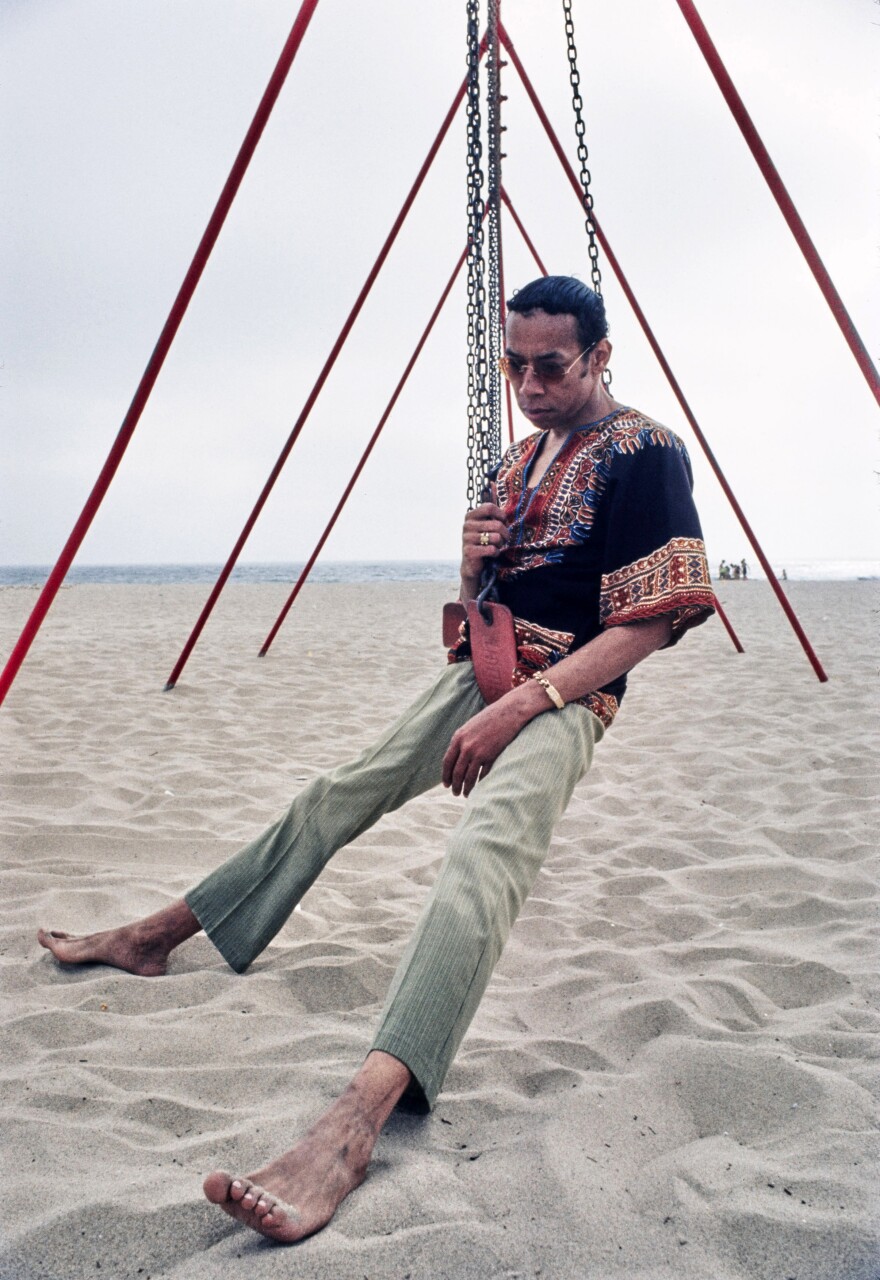

Jackie McLean

John H. Armwood Jazz History Lecture Nashville's Cheekwood Arts Center 1989

Wednesday, December 15, 2021

Sunday, December 12, 2021

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

Monday, November 15, 2021

Friday, November 12, 2021

Saturday, November 06, 2021

Thursday, November 04, 2021

Wednesday, November 03, 2021

Wednesday, October 27, 2021

Sunday, October 24, 2021

Saturday, October 23, 2021

Friday, October 22, 2021

Thursday, October 21, 2021

Wednesday, October 20, 2021

What a Rare, Live ‘A Love Supreme’ Reveals About John Coltrane - The New York Times

What a Rare, Live ‘A Love Supreme’ Reveals About John Coltrane

"A long-buried private recording of the suite, captured in October 1965, allows listeners to experience more sides of the musician than some major albums in his catalog.

When John Coltrane released “A Love Supreme” in early 1965, fans recognized it as a masterwork practically on first listen. Best-of-the-year accolades rolled in. It became the biggest commercial hit of his career, and possibly the most timeless piece of worship music in the American canon.

“A Love Supreme” was a realized ideal: Its four-part suite perfectly melded spiritual transcendence and physical exertion, powerful composition and openhearted improvising. And as soon as it was released, Coltrane was ready to leap ahead far further.

He started expanding the classic quartet that had recorded the album until the group reached a breaking point. He brought in other, often-younger musicians and guided them into furious improvisations, drawing upon spiritual traditions from across the Global South. And he rarely returned to “A Love Supreme.”

Until this week, only one known live recording of it had been released, from a performance in Antibes, France, in mid-1965. But on Friday, Impulse! Records will put out a long-buried private recording, “A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle,” captured in October of that year at the Penthouse jazz club.

It’s a landmark discovery. Over the course of the extended 75 minutes of the suite, we experience more sides of Coltrane than on some major albums in his catalog.

Coltrane would later look back on this brief moment in his career with a special fondness, and some longing. His classic quartet — one of the most revered groups in the history of jazz — was still intact, but he had taken to attacking its equilibrium, infusing it constantly with fresh blood.

“I was trying to do something,” Coltrane told the critic Frank Kofsky in late 1966, by which point the drummer Elvin Jones and the pianist McCoy Tyner had ditched the group. “I figured I could do two things: I could have a band that played like the way we used to play, and a band that was going in the direction that the one I have now is going. I could combine these two, you know, with these two concepts going. And it could have been done.”

Actually, it was done, for a limited stretch of 1965 — more or less from the assassination of Malcolm X, in February, to the first major escalation of American warfare in Vietnam, in November. Touring the West Coast that fall, Coltrane spent a week at the Penthouse in Seattle, with his quartet augmented by a second bassist, Donald Rafael Garrett, and a second tenor saxophonist, Pharoah Sanders, both of whom had joined the band during its prior tour stop, in San Francisco. (Coltrane had just invited Sanders in as a permanent member, which he would remain until Coltrane’s death in 1967, from cancer, at age 40.)

Another album from Coltrane’s run that week, titled “Live in Seattle,” came out a few years after his death. Recorded that Thursday night, Sep. 30, it features epic-scale renditions of his originals, and jazz standards turned over. While he recorded prolifically during this period, it was until this week the only live club date from 1965 released as an album.

On Saturday, Oct. 2, Coltrane invited the young alto saxophonist Carlos Ward, who had been part of the local matinee band at the Penthouse, to join his group as a seventh member that evening. The daytime band had been led by Joe Brazil, a saxophonist and prominent bandleader on the Seattle jazz scene, who died in 2008. An inveterate reel-to-reel tape user, Brazil recorded his own performance that day, and Coltrane’s that night, on the club’s house system.

The recordings were high-enough quality for an audio team to successfully restore them, and the final product’s sound is relatively clear, with only the two basses sometimes winding up muffled.

The tapes languished in Brazil’s basement for years. It wasn’t until Steve Griggs, another area saxophonist, gained permission from Brazil’s widow, Virginia, to sort through his collection that the “A Love Supreme” reel surfaced.

Griggs set about bringing his uncle’s old Akai reel-to-reel player back to working order. “Finally when I did get it working and I could listen to the tapes, I started looking through the Coltrane material, and there was this one tape that said, ‘Coltrane … A Love’ on the box,” Griggs remembered in an interview.

He had stepped into Joe and Virginia Brazil’s basement hoping to find clues into Coltrane’s historic week in Seattle, thinking he might write something about it. He got more than he’d imagined possible. “This recording has kind of exceeded my wildest dreams of making that scene come alive on paper,” he said.

The first notes of the suite he heard were from “Psalm,” its last movement, the tenderest part: a praise poem, addressed directly to God, that Coltrane had set to music and played through his saxophone. The poem itself is printed in the original album’s liner notes.

In Seattle, he chops up and reorders the melody, lingering on and repeating certain phrases (like he did in France, on the other live recording). With Coltrane the lone saxophone on this track, it’s a respite after more than an hour of soaring and crashing, hard-blown notes over Jones’s polyrhythmic waves. Griggs didn’t know about all that until he flipped the tape, and played it back from the beginning.

In concert Coltrane was known for pushing himself, and his horn, to the physical limits. It is part of what drew him to Sanders, whose role in the group was largely to provide atonal cries and expressionist sounds (what today would be called extended technique, but his critics often called noise).

Coltrane’s studio albums, including “A Love Supreme,” had included more digestible helpings of spitfire improvising, held to the ballast of his quartet. That would change with “Ascension,” a howling large-ensemble session that Coltrane recorded at Rudy Van Gelder Studios in summer 1965, shortly before leaving for the West Coast tour, and that Impulse! would release the following year.

“Ascension” marked the beginning of Coltrane’s final period. Having written jazz’s major composition with “A Love Supreme,” he now fled from musical prescription.

But on “A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle,” he pushes in both directions. It’s clear from the recording that these musicians hadn’t rehearsed the suite, and some didn’t know it by heart. He gives verbal cues here and there, and at times he has to use the magnetism of his horn to yank the group back to center. He does this on the up-tempo minor swing of “Resolution” and “Pursuance,” blowing the melodies in strong, controlled gusts, in sync with the multilevel machinery of Jones’s swing feel.

The pianist and Coltrane scholar Lewis Porter, who contributed to the new album’s liner notes, marveled at Coltrane’s ability to balance an expert’s rigor with a beginner’s mind. “How do you square the world’s most amazing saxophonist — who’s always practicing, partly out of fanaticism, but partly just to get better — with a guy that says, ‘Let’s all get together and play “A Love Supreme,” even if you don’t know how it goes?’” Porter said in an interview.

He noted that Coltrane had credited Miles Davis with convincing him that rehearsals stifle creativity, rather than draw it out. To a sometimes extreme degree, Porter said, Coltrane “took Miles’s message to heart.”

The saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, 24, is high on the list of young jazz innovators today, and like Coltrane sees both composing and improvising as something akin to a form of worship. Growing up in Philadelphia, where Coltrane spent his formative years, Wilkins came to know the sacred music of “A Love Supreme” via jam sessions, where musicians would call “Resolution” and “Pursuance” along with Broadway standards, injecting a reverent current into the space.

“There was a general common knowledge onstage that we were reaching for something high,” Wilkins said. “This wasn’t a personal thing; you could feel it on the bandstand. You weren’t done soloing till you felt we had, not even peaked, but reached a transcendent level.”

Listening to the newly unearthed recording, Wilkins said that in Coltrane’s push toward a freer aesthetic, he heard a group of musicians reaching escape velocity. “I wonder if they were thinking of the audience in these moments,” he said, considering the nearly 300 paying guests who were gathered at the Penthouse that night.

“I don’t think they were,” Wilkins said. “I think they completely escaped surveillance.”

Sunday, October 17, 2021

Saturday, October 16, 2021

Friday, October 08, 2021

Sunday, October 03, 2021

Opinion | Jan. 6 Was Worse Than We Knew - The New York Times

Jan. 6 Was Worse Than We Knew

The editorial board is a group of opinion journalists whose views are informed by expertise, research, debate and certain longstanding values. It is separate from the newsroom.

However horrifying the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol appeared in the moment, we know now that it was far worse.

The country was hours away from a full-blown constitutional crisis — not primarily because of the violence and mayhem inflicted by hundreds of President Donald Trump’s supporters but because of the actions of Mr. Trump himself.

In the days before the mob descended on the Capitol, a corollary attack — this one bloodless and legalistic — was playing out down the street in the White House, where Mr. Trump, Vice President Mike Pence and a lawyer named John Eastman huddled in the Oval Office, scheming to subvert the will of the American people by using legal sleight-of-hand.

Mr. Eastman’s unusual visit was reported at the time, but a new book by the Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Robert Costa provides the details of his proposed six-point plan. It involved Mr. Pence rejecting dozens of already certified electoral votes representing tens of millions of legally cast ballots, thus allowing Congress to install Mr. Trump in a second term.

Mr. Pence ultimately refused to sign on, earning him the rage of Mr. Trump and chants of “Hang Mike Pence!” by the rioters, who erected a makeshift gallows on the National Mall.

The fact that the scheme to overturn the election was highly unlikely to succeed is cold comfort. Mr. Trump remains the most popular Republican in the country; barring a serious health issue, the odds are good that he will be the party’s nominee for president in 2024. He also remains as incapable of accepting defeat as he has ever been, which means the country faces a renewed risk of electoral subversion by Mr. Trump and his supporters — only next time they will have learned from their mistakes.

That leaves all Americans who care about preserving this Republic with a clear task: Reform the federal election law at the heart of Mr. Eastman’s twisted ploy, and make it as hard as possible for anyone to pull a stunt like that again.

The Electoral Count Act, which passed more than 130 years ago, was Congress’s response to another dramatic presidential dispute — the election of 1876, in which the Republican Rutherford Hayes won the White House despite losing the popular vote to his Democratic opponent, Samuel Tilden.

After Election Day, Tilden led in the popular vote and in the Electoral College. But the vote in three Southern states — South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana — was marred by accusations of fraud and intimidation by both parties. Various officials in each state certified competing slates of electors, one for Hayes and one for Tilden. The Constitution said nothing about what to do in such a situation, so Congress established a 15-member commission to decide which electors to accept as valid.

The commission consisted of 10 members of Congress, evenly divided between the parties, and five Supreme Court justices, two appointed by Democrats and three by Republicans. Hayes, the Republican candidate, won all the disputed electors (including one from Oregon) by an 8-to-7 vote — giving him victory in the Electoral College by a single vote.

Democrats were furious and began to filibuster the counting process, but they eventually accepted Hayes’s presidency in exchange for the withdrawal of the last remaining federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction and beginning the era of Jim Crow, which would last until the middle of the 20th century.

It was obvious that Congress needed clearer guidelines for deciding disputed electoral votes. In 1887, the Electoral Count Act became law, setting out procedures for the counting and certifying of electoral votes in the states and in Congress.

But the law contains numerous ambiguities and poorly drafted provisions. For instance, it permits a state legislature to appoint electors on its own, regardless of how the state’s own citizens voted, if the state “failed to make a choice” on Election Day. What does that mean? The law doesn’t say. It also allows any objection to a state’s electoral votes to be filed as long as one senator and one member of the House put their names to it, triggering hours of debate — which is how senators like Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley were able to gum up the workson Jan. 6.

A small minority of legal scholars have argued that key parts of the Electoral Count Act are unconstitutional, which was the basis of Mr. Eastman’s claim that Mr. Pence could simply disregard the law and summarily reject electors of certain key battleground states.

Nothing in the Constitution or federal law gives the vice president this authority. The job of the vice president is to open the envelopes and read out the results, nothing more. Any reform to the Electoral Count Act should start there, by making it explicit that the vice president’s role on Jan. 6 is purely ministerial and doesn’t include the power to rule on disputes over electors.

The law should also be amended to allow states more time to arrive at a final count, so that any legal disputes can be resolved before the electors cast their ballots.

The “failed” election provision should be restricted to natural disasters or terrorist attacks — and even then, it should be available only if there is no realistic way of conducting the election. Remember that the 2012 election was held just days after Hurricane Sandy lashed the East Coast, and yet all states were able to conduct their elections in full. (This is another good argument for universal mail-in voting, which doesn’t put voters at the mercy of the weather.) The key point is that a close election, even a disputed one, is not a failed election.

Finally, any objection to a state’s electoral votes should have to clear a high bar. Rather than just one member of each chamber of Congress, it should require the assent of one-quarter or more of each body. The grounds for an objection should be strictly limited to cases involving clear evidence of fraud or widespread voting irregularities.

The threats to a free and fair presidential election don’t come from Congress alone. Since Jan. 6, Republican-led state legislatures have been clambering over one another to pass new laws making it easier to reject their own voters’ will, and removing or neutralizing those officials who could stand in the way of a naked power grab — like Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, did when he resisted Mr. Trump’s personal plea to “find” just enough extra votes to flip the outcome there.

How to ensure that frivolous objections are rejected while legitimate ones get a hearing? One approach would be to establish a panel of federal judges in each state to hear any challenges to the validity or accuracy of that state’s election results. If the judges determine that the results are invalid, they would lay out their findings in writing and prevent the state from certifying its results.

There is plenty more to be done to protect American elections from being stolen through subversion, like mandating the use of paper ballots that can be checked against reported results. Ideally, fixes like these would be adopted promptly by bipartisan majorities in Congress, to convey to all Americans that both parties are committed to a fair, transparent and smooth vote-counting process. But for that to happen, the Republican Party would need to do an about-face. Right now, some Republican leaders in Congress and the states have shown less interest in preventing election sabotage than in protecting and, in some cases, even venerating the saboteurs.

Democrats should push through these reforms now, and eliminate the filibuster if that’s the only way to do so. If they hesitate, they should recall that a majority of the Republican caucus in the House — 139 members — along with eight senators, continued to object to the certification of electoral votes even after the mob stormed the Capitol.

Time and distance from those events could have led to reflection and contrition on the part of those involved, but that’s not so. Remember how, in the frantic days before Jan. 6, Mr. Trump insisted over and over that Georgia’s election was rife with “large-scale voter fraud”? Remember how he called on Mr. Raffensperger to “start the process of decertifying the election” and “announce the true winner”? Only those words aren’t from last year. They appear in a letter Mr. Trump sent to Mr. Raffensperger two weeks ago.

Mr. Trump may never stop trying to undermine American democracy. Those who value that democracy should never stop using every measure at their disposal to protect it."

Wednesday, September 29, 2021

Tuesday, September 28, 2021

Dr. Lonnie Smith, Master Of The Hammond Organ, Dies At 79 : NPR

Dr. Lonnie Smith, Master Of The Hammond Organ, Dies At 79

Greg Bryant

Dr. Lonnie Smith.

"Dr. Lonnie Smith, an NEA Jazz Master known for his dynamism and wizardry on the Hammond B3 organ, died Tuesday. He was 79 years old.

His death was confirmed on Twitter by Blue Note Records.

Smith was one of the most unique Hammond stylists to emerge from the golden era of 1960s organ ensembles, a scene that had its roots in Black American neighborhood venues. Early in his career, he was lauded for his work in guitarist George Benson's first quartet and subsequently for his involvement with saxophonist Lou Donaldson's groups.

Musically, Smith wove an other-worldly and soulful tapestry that joined relentlessly grooving bass lines with stirring melodies and harmonies. As a band leader and performer, Smith had a spirited and visceral performance style that allowed him to garner fans around the world.

Offstage, Smith was affable and engaging with a healthy sense of humor. At concerts, the turban and tunic clad organist would unassumingly stroll onto the stage with one of his signature canes and waste no time. Almost immediately, all four of Smith's limbs would begin dancing, almost magically, at the Hammond organ's console.

Smith was born in Lackawanna, N.Y., a suburb of Buffalo, on July 3, 1942. His mother introduced him to gospel, blues, jazz and early rhythm and blues. As a teenager in the 1950s, Smith began learning music by ear and played trumpet and other brass instruments in school. He also began singing at local venues throughout Buffalo in a doo wop group known as The Supremes, an ensemble that predated the award-winning Motown all-female group that followed.

After a brief stint in the Air Force, Smith returned home to Buffalo in the early 1960s, at which point he began listening closely to Blue Note star organist Jimmy Smith. The pull to become a musician became stronger, but he had not decided on an instrument. Around that same time, he began frequenting a music store owned by local accordion player Art Kubera, who would have a catalyzing effect on Smith's career.

"One day the owner [Kubera] said 'Son, why do you sit here every day until closing time?'" Smith recalled in conversation with the National Endowment for The Arts. "I told him, 'Sir, if I had an instrument I could work, and if I could work, I could make a living.' One day I went there, and he closed the place. We went to his house in the back, and there was a brand-new Hammond organ. He told me, 'If you can get this out of here, then it's yours.' It was snowing in Buffalo, but I did. Art was my angel."

After a neighbor taught him how to power up the organ and navigate its stops and drawbars, Smith began playing and his growth on the instrument was uncannily rapid. Barely a year into his development, he began playing in house bands in the Midwest, New York City and in Buffalo. Many of the groups Smith performed in were backing bands for soul singers and instrumentalists on the touring circuit. In 1964, Smith broke onto the international jazz scene when organist Jack McDuff's young guitarist, George Benson, resigned his position and formed a group of his own. Benson secured Smith for the organ chair in his new quartet. After their residencies at Harlem's Palm Cafe and Minton's Playhouse that same year, both Benson and Smith were signed by Columbia Records and made albums as leaders. They established a new style that joined blistering bebop with new rhythm and blues. The music was danceable, yet it contained the language of the jazz tradition. When saxophonist Lou Donaldson hired Smith and Benson for 1967's Blue Note smash Alligator Boogaloo, the result was a surprise jukebox hit whose title track landed on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

YouTube

This success set the stage for Smith to be signed by Blue Note as a band leader in 1968. Within two years, the organist cut five albums for the label. He earned honors as Downbeat's "Top Jazz Organist" and his albums Think (1968) and Drives (1970) both earned spots on Billboard's R&B albums chart.

Smith left Blue Note records in 1971 and recorded albums for producers Creed Taylor and Sonny Lester off and on during the 1970s. He began to fade from the spotlight as the sound of popular music changed and Hammond organ-based music waned in popularity. During this time, he began to don his signature turbans. Though not explicitly religious, he wore them as a symbol of universal spirituality, love and respect. Smith also adopted the moniker "Dr." not as an indication of formal training, but to highlight his ability to serve as a unique practitioner of the music. (It also helped to create a distinction between him and fellow keyboardist Lonnie Liston Smith.) He worked briefly with Marvin Gaye, reconnected with George Benson and, by the mid 1980s, he rekindled his unique brand of swing on the Hammond organ with guitarists Richie Hart, Jimmy Ponder and Melvin Sparks, vocalist Etta James and drummer Alvin Queen.

YouTube

By the 1990s, the groove-based acid jazz movement broke out in London, England, and in the United States, hip-hop rejuvenated the beat-driven jazz of the late 1960s and early 1970s through sampling. As a result, Smith was again in demand as a featured guest artist and as a leader. He released a string of four critically acclaimed albums for Palmetto Records in the early 2000s that paired him with guitarists Peter Bernstein and Jonathan Kriesberg and drummers Gregory Hutchinson, Allison Miller, Herlin Riley and Jamire Williams.

Smith self-released two fiery albums in 2013 and 2014 before returning to the Blue Note fold in 2016. Over the next year, Smith was named as an NEA Jazz Master and made notable, cross-genre collaborations with Norah Jones and The Roots. Smith's final albums, All In My Mind and Breathe, were released in 2018 and 2021, respectively, and featured studio collaborations with Iggy Pop, along with magical in-concert explorations with his working band of Kriesberg, drummers Johnathan Blake or Joe Dyson, and horns."

Monday, September 27, 2021

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Sunday, September 19, 2021

Saturday, September 18, 2021

Thursday, September 09, 2021

Saturday, August 14, 2021

Thursday, August 12, 2021

Monday, August 09, 2021

Sunday, August 08, 2021

Thursday, August 05, 2021

Friday, July 30, 2021

Sunday, July 18, 2021

Friday, July 16, 2021

Sunday, July 04, 2021

Friday, July 02, 2021

Tuesday, June 29, 2021

Monday, June 28, 2021

Wednesday, June 23, 2021

Saturday, June 05, 2021

Thursday, June 03, 2021

The Beehive (Live (Saturday, July 11, 1970 - Set 2))

A Legendary Stand by the Lee Morgan Quintet Finally Sees Full Release, as 'The Complete Live at the Lighthouse'

Joel Franklin

/

Lee Morgan — one of WBGO's Top 100 artists, as selected by our listeners — was a trumpeter who led his share of combustible bands. When his Live At The Lighthouse was first reissued in the U.S. in 1996, many listeners had their first encounter with his working group of 1970, featuring reedist Bennie Maupin and the piano-bass-drums rhythm team of Harold Mabern, Jymie Merritt and Mickey Roker.

That collection expanded the original double-LP release from four extended tunes (each occupying one side of vinyl) to 13 tracks across three CDs. Morgan's band was a dynamically hard swinging quintet. They made their listeners feel every note as they explored a unique songbook of original compositions based in blues, bop, modal, odd meter and even a slight tinge of the avant-garde.

The liner notes for the 3-CD set contained a full chronological rundown of every night's set list. Ultimately, there were 12 sets recorded, and nearly four hours of the Lighthouse material still remained unissued. Would fans of the group ever get the chance to hear all of that material, as they had heard Miles Davis' The Complete Plugged Nickel Sessions or Bill Evans' Turn Out The Stars: The Final Village Vanguard Recordings?

The answer, finally, is yes. The Complete Live at the Lighthouse — a mammoth 12-LP or 8-CD set containing every note the group played over three nights of recording — will arrive July 30 on Blue Note Records. The label announced its release this morning, and released one track from the set: a previously unreleased version of "The Beehive."

Mabern wrote this song in dedication to a Chicago jazz landmark of the mid-1950s that featured performances by the likes of Charlie Parker, Clifford Brown and Max Roach. As Morgan's band captures the spirit and lineage of those icons and one of the many stages they soared from, the song is a showcase for their distinct group language.

From the first beat of Mickey Roker's take-no-prisoners drum intro through the tune's concluding fermata, all five musicians burn with a vengeance on "Beehive." Whereas the master version may have a firmer grasp on the melodic cues that trigger the chord changes during the solos, this "new" Beehive performance pushes a tad more aggressively with the rhythm, sizzling with an even rawer energy.

There is certainly a jubilation in the swing of Mabern, Merritt and Roker — but there's also a tension that carries through the entire performance. Performing in California was often cited by musicians at the time as a respite from the intensity of The Big Apple, but the playing on this track contains a New York pulse all the way. Maupin, on tenor saxophone, is relentless. His muscular sound and knack for combining rhythmic and exploratory sonic figures with the language of bebop distinguishes him alongside contemporaries like Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson and Wayne Shorter.

After Maupin comes Morgan. Straight out of the gate, he starts his solo journey with the same rhythmic figure that Roker used to end his drum break. Next, the trumpeter issues a dazzling combination of melodic fragments from the main melody that he recasts, pulls apart, and uses as launching pads for new ideas. Morgan was on the tail end of recovering his embouchure after an incident a year or so earlier, but he sounds firm and confident here. Most technically impressive are a few unbroken lines that echo the wizardry of Clifford Brown.

Perhaps the most incredible peak of this performance contains an occurrence just beneath the surface. When Morgan plays the cue that should announce the chord change, he plays it in the original key instead of the new one. At this tempo and energy level, Morgan's move may have caused a bobble (or an all out wreck) with lesser players, but he's in the best hands with this group. Mabern and Merritt stay with Morgan in the original key and he pours out even more ideas until he slightly disguises and recasts the cue again in the new key, and everyone moves seamlessly forward together. Morgan, Maupin, Mabern, Merritt and Roker are conducting the best possible clinic here, and their covert chops and listening are just as strong as their overt mastery."

Monday, May 24, 2021

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

Vincent Herring: Not the End of the Line The saxophonist’s life and livelihood were seriously threatened by the coronavirus, but he’s determined to carry on

Vincent Herring: Not the End of the Line

“After months of suffering from the impact of COVID-19 on the jazz economy, things got worse for alto saxophonist Vincent Herring: He contracted the disease itself.

“It felt like the flu,” he recalled in a recent interview. “I was tired all the time, but I wasn’t coughing, and I didn’t have any respiratory problems. After less than a week, I felt totally fine.” But Herring’s health troubles were just beginning. The COVID-19 aftereffects he suffered would last far longer, rendering him barely able to play his horn and almost forcing him to cancel the sessions that produced his latest recording on Smoke Sessions, Preaching to the Choir. The experience has given him a hard-won new perspective on a phenomenally successful career.

Herring’s COVID ordeal began last August. He traveled to Las Vegas to take part in a centennial celebration for Charlie Parker, the subject of his 2019 recording Bird at 100, a collaboration with fellow top-tier altoists Gary Bartz and Bobby Watson. Herring suspects that he contracted the disease on the flight back to New York. Although the symptoms of the potentially lethal virus didn’t fell him, before long he was feeling something else: pain in his joints.

Initially, the 56-year-old saxophonist chalked up this new discomfort to the vagaries of aging. “I remembered some comedian talking about when you get to be over 50 you get aches and pains, and when you tell the doctor they’re just like, ‘Yeah, it happens,’” he said. “So I didn’t think anything of it. But then it got progressively worse. My doctor had me do a blood test and she told me I had rheumatoid arthritis. And it was a gift from COVID.” Worse still, some of the most severe pain was in his fingers.

What followed was a nightmarish succession of doctor recommendations and specialists in joint inflammation. The specialists disagreed on the dosage of a steroid. Herring’s kids got involved researching remedies too. Meanwhile, on a scale of one to 10 “where 10 [means] jumping out of a window because you’re in so much pain,” Herring said he was a nine.

Finally, after weeks of trial and error, Herring’s physicians settled on an approach. He smiled as he described it. “My pain and discomfort level is controlled, through a medication cocktail,” he said, holding up one hand as if in triumph. “That works for me, as long as I take it on time, everything’s good to go,” he added with a sheepish smile. “And of course you learn to take it, because the pain threshold goes up very quick. Right now, I’m feeling okay because I took medication and, just as important, my fingers are working well. But boy, it sure is a thin line between that and catastrophe.”

“MY LIFE AS A JAZZ ARTIST IS OVER”

Adding to the drama of the situation was that Herring was in the middle of recording Preaching to the Choir. Some of the tracks for the album—which features stellar accompaniment by pianist Cyrus Chestnut, bassist Yasushi Nakamura, and drummer Johnathan Blake—were already in the can, but a second session had been planned. Suddenly, Herring was uncertain he could manage it.

In the end, he said, “we made that second date, but I didn’t record as many original compositions as I wanted. Was I in my absolute peak form for playing saxophone? No, because I couldn’t practice but a little bit, but I was overcome with joy that I could play. So that added a sense of purpose to the recording—you know, I’m grateful to be able to do it.”

Before hitting the studio, he got dire news from his physician. “My doctor told me there’s no cure. No cure.” During our interview, he grimly shook his head when repeating those words for the second time. “So I’m sitting there thinking, well, my life as a jazz artist is over.”

Herring thought of the great pianist Donald Brown, his friend for many years, whose performing career was cut short by rheumatoid arthritis and rotator cuff surgeries. “I never really got it until I was confronted with the same thing. I don’t want to say I was super-depressed; it was just another turn in your life, you know?” But he felt the existential threat, and he began thinking about alternatives: “I felt like, ‘Man, I’m gonna have to do something else in life, what else can I do?’”

Over the last couple of years, Herring had enjoyed some success trading stocks, so he figured he could sustain himself that way. “Nevertheless, it was still really jarring to think that your life’s going to change that much. It was bad enough that I was going through a divorce and just getting over that.” He paused for a second and smiled. “It’s funny—my ex and I, we don’t really speak. But when the kids told her about this, she actually reached out to me!”

He is reflective about the experience. “It centers your purpose on music. I don’t want to say it makes it urgent, but it definitely puts another level on it, you know, both as a player and performer. And then you have the depression, of not being able to play and perform. As many goals as I’ve fulfilled, there’s still things that I want to do. And I still have goals that I can reach. I feel like I’ve been given a second chance.”

I understood the message. Seven years ago, I’d faced down similar fears. Journalism, my bread and butter for three decades, had all but vanished from my personal economy, and the food business, my preferred means of alternative income, had grown dicey; in addition to that, the rigors of being on my feet all the time—a necessity in the food biz—felt far different than it had in my thirties. The gigs that used to help me make ends meet instead seemed to be killing me. By 2014, I was walking with a cane most of the time, wondering how I would work next week, much less next month or year. I made it through in part by recalling the energy from happier days, and Herring’s music recalls those days too. Much of his new album bristles with the same kind of energy that I loved in my early New York City jazz experiences, attending free shows in the late ’70s and early ’80s sponsored by Jazzmobile, where players preached, if not to the choir, then with impassioned aim to convert newcomers.“

Monday, May 10, 2021

Sunday, May 02, 2021

Saturday, May 01, 2021

Tuesday, April 27, 2021

Wednesday, April 07, 2021

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Thursday, March 18, 2021

Beyond the pandemic, Asian American leaders fear U.S. conflict with China will fan racist backlash. This is happened before. Anti-Asian racism let to the Chinese exclusion act of 1882 which was used to ban all East Americans. Even today most Americans are not sophisticated enough to be able to distinguish between a Chinese, a Korean and a Japanese etc. Lack of exposure and ignorance are as American as apple pie. They don’t all look alike. “ Beyond the pandemic, Asian American leaders fear U.S. conflict with China will fan racist backlash David Nakamura Carol Narasaki listens to speakers during a protest organized by the Asian American Pacific Islanders Organizing Coalition Against Hate and Bias in Seattle. (Lindsey Wasson/Reuters) President Biden has sought to blunt a reported surge in anti-Asian bias incidents by ordering the federal government not to use xenophobic language to describe the coronavirus and by calling “vicious hate crimes” during the pandemic “un-American.” But Asian American leaders are warning that a deepening geopolitical confrontation between the United States and China is contributing to the heightened suspicion, prejudice and violence against their communities in ways that could continue to intensify even after the pandemic begins to subside. Advocates called Biden’s rhetorical efforts a welcome corrective to President Donald Trump, who railed against the “China virus” and “kung flu.” Yet the broadening conflict among the world’s two largest economies — on trade, defense, 5G networks, cybersecurity, the environment, health security and human rights — has contributed to a growing number of Americans calling China the “greatest enemy” of the United States, according to a Gallup poll this week. In the survey, 45 percent of respondents named China as the top threat, more than twice as many as a year earlier, when the country was ranked on par with Russia. Democrats and Republicans have voiced bipartisan support for a tougher U.S. policy, including economic sanctions on Beijing over cyber-intrusions, human rights violations and crackdowns on democracy in Hong Kong. “When America China-bashes, then Chinese get bashed, and so do those who look Chinese. American foreign policy in Asia is American domestic policy for Asians,” said Russell Jeung, a history professor at San Francisco State University who last year helped found Stop AAPI Hate (AAPI stands for Asian American and Pacific Islanders). The advocacy group has tallied more than 3,000 incidents of bias and hate during the pandemic. “The U.S.-China cold war — and especially the Republican strategy of scapegoating and attacking China for the virus — incited racism and hatred toward Asian Americans,” Jeung said. Politicians reacted on March 17 to the shootings at three Atlanta-area spas that left eight people dead, including six Asian women. (Joy Yi/The Washington Post) Anti-Asian attacks rise along with online vitriol A number of violent assaults on Asian Americans over the past two months, including some that went viral after being caught on video, have drawn political and media attention to escalating fears over public safety. The slaying of eight people, including six women of Asian descent, at three Georgia spas on Tuesday sparked demands for an urgent response from authorities. Police arrested Robert Aaron Long, a White man, in connection with the killings and cited as a potential motive Long’s interest in eliminating “sexual temptation.” Suspect charged with killing 8 in Atlanta-area shootings that targeted Asian-run spas Not all of the cases appear to have a link to anger over the pandemic or were necessarily motivated by racial resentment. But advocates said they have collected enough anecdotal evidence through self-reporting portals set up last year by community groups to illustrate that attacks are spiking. And they are fearful that the intensifying competition between Washington and Beijing is contributing to scapegoating of Asian Americans in echoes of earlier periods of widespread hostility during geopolitical tumult and heightened nationalism in the United States. They pointed to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that banned the immigration of Chinese laborers amid national economic anxiety, the internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, and attacks on mosques and Muslim Americans in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. “For as long as Asians have been in America, we’ve been scapegoated, treated as outsiders and seen as untrustworthy. Too often, these prejudices are exploited for political gain,” said Christopher Lu, who served as White House Cabinet secretary and deputy labor secretary in the Obama administration. “As troubling as our current situation is, I am concerned that things are going to get much worse as U.S.-China tensions grow.” Asian American leaders acknowledged the need for the United States to develop a tougher strategy to counter the Chinese Communist Party’s influence campaign across the globe. The question, activists said, is how the federal government and elected officials speak publicly about the challenge and how far they go to counter it. Trump sought to blame Beijing for the outbreak of the pandemic, employing xenophobic language that was echoed by his supporters and other Republican officials and condemned by Democrats. But in April, weeks after the onset of the pandemic, Biden also drew heat from Democratic Congress members and community groups for a campaign advertisement that accused the 45th president of having “rolled over for the Chinese” in managing the coronavirus and cast China as a looming threat. Biden’s campaign apologized for the language and aired a revised version of the ad. But the episode illustrated the intensifying effort of both parties to appear tougher on Beijing. “It is clearly a difficult line to walk. However, I do believe there is a way of disagreeing with China’s policies without denigrating the Chinese people themselves,” said Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.), chair of the House Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. Attacks on Asian Americans during pandemic renew criticism that U.S. undercounts hate crimes Chu praised Biden for issuing an executive action in January aimed at barring federal agencies from blaming China for the pandemic and instructing the Justice Department to improve data collection on hate crimes. In a prime-time address to the nation last week about his administration’s coronavirus response, Biden decried attacks and harassment against Asian Americans who have been “forced to live in fear for their lives just walking down streets.” “It must stop,” Biden said. White House aides, including domestic policy adviser Susan Rice and senior adviser Cedric L. Richmond, met virtually with Asian American advocacy groups two weeks ago to hear their concerns. They pledged to use the power of the administration to combat violence but offered few specifics, according to activists who participated, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a private conversation. Chu and others have pushed Biden to elevate more Asian Americans to high-level jobs in his administration, noting there is only one Cabinet-level official of East Asian descent, Katherine Tai, who was confirmed Wednesday as U.S. trade representative. Attorney General Merrick Garland met with advocates on a video call Wednesday that lasted about 45 minutes, telling them he recognized that regardless of whether the Georgia killings were racially motivated, he understood the larger context in which the crime took place and the sense of alarm within the community, according to a person who participated. Asian American leaders have raised questions about the Justice Department’s “China Initiative” — launched by the Trump administration in 2018 — to amplify ongoing U.S. government efforts to counter the Chinese government’s attempts to steal billions of dollars a year in U.S. intellectual property. Advocates have said the program has led to unfair racial profiling of scientists and academics of Chinese descent. They pointed to the case of University of Kansas researcher Franklin Tao, a permanent U.S. resident who was indicted in 2019 and accused of failing to disclose an alleged teaching contract with a Chinese university while conducting federally funded research. His lawyers have denied the charges. “Publicly available information suggests at least 60 cases that have been filed had a reference to the China Initiative. Only a quarter of them have actually involved charges of espionage,” said John C. Yang, executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, which has advocated on behalf of Tao, whose case is pending. Yang’s organization has asked the Biden administration to put a moratorium on the program and conduct a review of it. “This goes to the perpetual foreigner stereotype we always talk about,” Yang said, “where in various points in history, we are targeted unfairly.” Justice Department officials met with Asian American advocates two weeks ago, but they declined to comment on the future of that program. They have pledged to develop new grant programs for local police agencies to report on hate crime data and efforts to translate federal hate crime reporting portals into Chinese and other Asian languages. At her confirmation hearing last week, Lisa Monaco, Biden’s nominee for deputy attorney general, offered credit to the Trump administration for focusing on cyberthreats from China and said she expects to “double down” on the strategy. “This is an area I think we have a great deal more to do,” she told senators. On Wednesday, the Biden administration announced economic sanctions against two dozen Chinese and Hong Kong officials. The move came in advance of Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s first meeting with Chinese counterparts in Alaska later this week. Last week, during a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) asked Blinken about concerns among some advocacy groups that restrictions on assignments for U.S. diplomats has disproportionately blocked Asian American Foreign Service officers from work in Asian countries. “It sends a false message that people who look like me would be more disloyal,” Lieu told Blinken, who said he shared the concerns about inequities in the system. “As you manage the relationship with China, I want to remain vigilant that fear of a foreign country does not negatively impact the Asian Americ

Beyond the pandemic, Asian American leaders fear U.S. conflict with China will fan racist backlash

President Biden has sought to blunt a reported surge in anti-Asian bias incidents by ordering the federal government not to use xenophobic language to describe the coronavirus and by calling “vicious hate crimes” during the pandemic “un-American.”

But Asian American leaders are warning that a deepening geopolitical confrontation between the United States and China is contributing to the heightened suspicion, prejudice and violence against their communities in ways that could continue to intensify even after the pandemic begins to subside.

Advocates called Biden’s rhetorical efforts a welcome corrective to President Donald Trump, who railed against the “China virus” and “kung flu.” Yet the broadening conflict among the world’s two largest economies — on trade, defense, 5G networks, cybersecurity, the environment, health security and human rights — has contributed to a growing number of Americans calling China the “greatest enemy” of the United States, according to a Gallup poll this week.

In the survey, 45 percent of respondents named China as the top threat, more than twice as many as a year earlier, when the country was ranked on par with Russia. Democrats and Republicans have voiced bipartisan support for a tougher U.S. policy, including economic sanctions on Beijing over cyber-intrusions, human rights violations and crackdowns on democracy in Hong Kong.

“When America China-bashes, then Chinese get bashed, and so do those who look Chinese. American foreign policy in Asia is American domestic policy for Asians,” said Russell Jeung, a history professor at San Francisco State University who last year helped found Stop AAPI Hate (AAPI stands for Asian American and Pacific Islanders). The advocacy group has tallied more than 3,000 incidents of bias and hate during the pandemic.

“The U.S.-China cold war — and especially the Republican strategy of scapegoating and attacking China for the virus — incited racism and hatred toward Asian Americans,” Jeung said.

A number of violent assaults on Asian Americans over the past two months, including some that went viral after being caught on video, have drawn political and media attention to escalating fears over public safety. The slaying of eight people, including six women of Asian descent, at three Georgia spas on Tuesday sparked demands for an urgent response from authorities. Police arrested Robert Aaron Long, a White man, in connection with the killings and cited as a potential motive Long’s interest in eliminating “sexual temptation.”

Not all of the cases appear to have a link to anger over the pandemic or were necessarily motivated by racial resentment. But advocates said they have collected enough anecdotal evidence through self-reporting portals set up last year by community groups to illustrate that attacks are spiking.

And they are fearful that the intensifying competition between Washington and Beijing is contributing to scapegoating of Asian Americans in echoes of earlier periods of widespread hostility during geopolitical tumult and heightened nationalism in the United States.

They pointed to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that banned the immigration of Chinese laborers amid national economic anxiety, the internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, and attacks on mosques and Muslim Americans in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

“For as long as Asians have been in America, we’ve been scapegoated, treated as outsiders and seen as untrustworthy. Too often, these prejudices are exploited for political gain,” said Christopher Lu, who served as White House Cabinet secretary and deputy labor secretary in the Obama administration. “As troubling as our current situation is, I am concerned that things are going to get much worse as U.S.-China tensions grow.”

Asian American leaders acknowledged the need for the United States to develop a tougher strategy to counter the Chinese Communist Party’s influence campaign across the globe. The question, activists said, is how the federal government and elected officials speak publicly about the challenge and how far they go to counter it.

Trump sought to blame Beijing for the outbreak of the pandemic, employing xenophobic language that was echoed by his supporters and other Republican officials and condemned by Democrats.

But in April, weeks after the onset of the pandemic, Biden also drew heat from Democratic Congress members and community groups for a campaign advertisement that accused the 45th president of having “rolled over for the Chinese” in managing the coronavirus and cast China as a looming threat.

Biden’s campaign apologized for the language and aired a revised version of the ad. But the episode illustrated the intensifying effort of both parties to appear tougher on Beijing.

“It is clearly a difficult line to walk. However, I do believe there is a way of disagreeing with China’s policies without denigrating the Chinese people themselves,” said Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.), chair of the House Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus.

Chu praised Biden for issuing an executive action in January aimed at barring federal agencies from blaming China for the pandemic and instructing the Justice Department to improve data collection on hate crimes. In a prime-time address to the nation last week about his administration’s coronavirus response, Biden decried attacks and harassment against Asian Americans who have been “forced to live in fear for their lives just walking down streets.”

“It must stop,” Biden said.

White House aides, including domestic policy adviser Susan Rice and senior adviser Cedric L. Richmond, met virtually with Asian American advocacy groups two weeks ago to hear their concerns. They pledged to use the power of the administration to combat violence but offered few specifics, according to activists who participated, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a private conversation.

Chu and others have pushed Biden to elevate more Asian Americans to high-level jobs in his administration, noting there is only one Cabinet-level official of East Asian descent, Katherine Tai, who was confirmed Wednesday as U.S. trade representative.

Attorney General Merrick Garland met with advocates on a video call Wednesday that lasted about 45 minutes, telling them he recognized that regardless of whether the Georgia killings were racially motivated, he understood the larger context in which the crime took place and the sense of alarm within the community, according to a person who participated.

Asian American leaders have raised questions about the Justice Department’s “China Initiative” — launched by the Trump administration in 2018 — to amplify ongoing U.S. government efforts to counter the Chinese government’s attempts to steal billions of dollars a year in U.S. intellectual property.

Advocates have said the program has led to unfair racial profiling of scientists and academics of Chinese descent. They pointed to the case of University of Kansas researcher Franklin Tao, a permanent U.S. resident who was indicted in 2019 and accused of failing to disclose an alleged teaching contract with a Chinese university while conducting federally funded research. His lawyers have denied the charges.

“Publicly available information suggests at least 60 cases that have been filed had a reference to the China Initiative. Only a quarter of them have actually involved charges of espionage,” said John C. Yang, executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, which has advocated on behalf of Tao, whose case is pending. Yang’s organization has asked the Biden administration to put a moratorium on the program and conduct a review of it.

“This goes to the perpetual foreigner stereotype we always talk about,” Yang said, “where in various points in history, we are targeted unfairly.”

Justice Department officials met with Asian American advocates two weeks ago, but they declined to comment on the future of that program. They have pledged to develop new grant programs for local police agencies to report on hate crime data and efforts to translate federal hate crime reporting portals into Chinese and other Asian languages.

At her confirmation hearing last week, Lisa Monaco, Biden’s nominee for deputy attorney general, offered credit to the Trump administration for focusing on cyberthreats from China and said she expects to “double down” on the strategy. “This is an area I think we have a great deal more to do,” she told senators.

On Wednesday, the Biden administration announced economic sanctions against two dozen Chinese and Hong Kong officials. The move came in advance of Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s first meeting with Chinese counterparts in Alaska later this week.

Last week, during a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) asked Blinken about concerns among some advocacy groups that restrictions on assignments for U.S. diplomats has disproportionately blocked Asian American Foreign Service officers from work in Asian countries.

“It sends a false message that people who look like me would be more disloyal,” Lieu told Blinken, who said he shared the concerns about inequities in the system. “As you manage the relationship with China, I want to remain vigilant that fear of a foreign country does not negatively impact the Asian American community.”