Cover of TutuCelebrating Miles Davis - 02/19/2011 | MiamiHerald.com

Cover of TutuCelebrating Miles Davis - 02/19/2011 | MiamiHerald.comBy the time of his death in 1991, trumpeter Miles Davis had lived several jazz lives.

Throughout a career spanning 50 years, Davis showed an acute sense for shifting musical paradigms and an uncanny ability to both absorb and transcend the musical trends of the day. Time and again, he reinvented himself as needed, and as he did, he also changed the sound of jazz.

Two sides of Davis’ music — one acoustic, featuring classic songs from albums such as Kind of Blue, the other electric, centering on Tutu, the most memorable studio recording of his late period — are the subject of Celebrating Miles, a concert featuring trumpeter (and Davis’ protégé) Wallace Roney, bassist-producer Marcus Miller, up-and-coming trumpeter Christian Scott and bassist Ron Carter, among others. The show, part of the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Art’s Jazz Roots series, takes place at the Knight Concert Hall at 8 p.m. Friday.

“It’s an honor to be part of a tribute to Miles, although I feel I pay tribute to him every time I play the trumpet,” Roney said in a recent phone interview. “I feel my own music is an extension of what he gave to the art form — but I think everybody’s music has been influenced by him.”

Roney’s career includes stints with Art Blakey, Tony Williams and Ornette Coleman, as well as 16 albums as a leader. He also won a Grammy in 1994 as a member of the Miles Davis Tribute Band, featuring Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Carter and Williams. He will perform in the acoustic half of the concert, leading an exceptional group comprised of Billy Childs on piano, Donald Harrison on alto sax, Javon Jackson on tenor sax, Carter on bass and Al Foster on drums.

Roney’s own music includes distinctly contemporary elements including turntables and down-tempo grooves. But he won’t approach this show like a repertory player performing a role.

“Playing Miles’ music is as much me as playing my own music. Playing Miles’ music is how I grew up, it’s how I’ve learned,” he says. “So it’s me. I don’t have to think ‘Well, now I’m going to role-play.’ All I have to do is go to that part of me.”

Jazz phenom

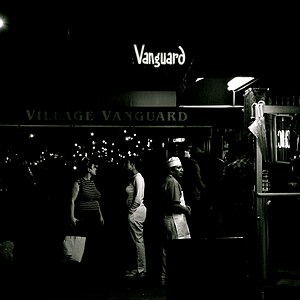

Roney, who will be 51 in May, was already being hailed as a young jazz phenom when he met Davis at a tribute to the trumpeter at the Bottom Line in New York City in 1983. After hearing him play, Davis took an interest and became his mentor. “He heard himself in me,” says Roney, matter-of-factly. “ ‘You remind me of me,’ he told me. ‘You look at me like I used to look at Dizzy.’ ”

In 1991, Davis invited Roney to be part of his concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. That evening, working with an orchestra conducted by Quincy Jones, Davis revisited some of the charts of his classic collaborations with arranger Gil Evans. Roney was a featured soloist.

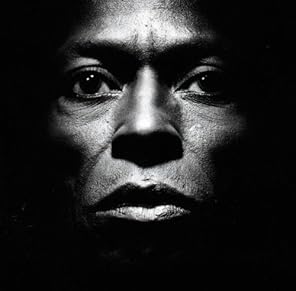

He chuckles as he discusses the perception and truth of Davis’ cultivated, forbidding persona.

“Miles had a vibe. He definitely had a vibe. He walked into a room and everybody would turn, and he knew how to use that to make people back away from him,” Roney says. “But he was a beautiful person. He was funny. He was friendly. He was generous. He was everything that people would love in a human being but, if you crossed him, oh buddy, ooooh buddy. Then you’d see the “Evil Miles Davis” — and I saw that, too.”

He says that often lost in Davis’ mystique is the fact that “this man was one of the greatest trumpet players of all time.”

“I got to hear his sound in my ear, and I never heard anybody sound like that in my life,” Roney says. “He had a sound that seemed to come from the clouds. I’m telling you. It was not from this Earth. It came from the clouds.”

For all of Davis’ tough posturing, his sound spoke with a touching vulnerability, which served him well in the ’50s and ’60s (just check his classic ballad playing), but also in the ’70s, as he stirred a witches’ brew of electric rock-jazz fusion.

A new groove

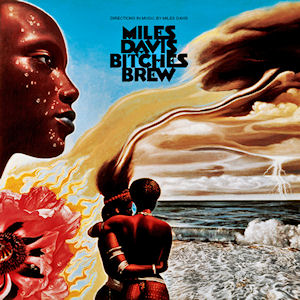

In Tutu, recorded 25 years ago this month, the deep humanity of Davis’ sound is set in a world of synthesizers and pre-programmed grooves. Here, he’s Everyman standing in a shiny, mechanical world of zeros and ones, smooth metal and plastic.

“That’s what I was hoping to get,” said Tutu co-producer Miller, 51, who wrote and arranged most of the songs, and played most of the instruments on the album. “To me it was the sound of someone who had been through so much, trying to make his way in this weird, technological world. Miles’ sound was perfect for that.”

The recording was strictly a studio affair. Co-producer Tommy LiPuma, then the head of jazz at Warner Bros., Davis’ new label, decided not to use a live band. To complement Miller’s work, additional musicians were called as needed. As for Davis’ involvement, Miller recalls that “Miles came in, heard the tracks and told me to call him when I needed the trumpet. That’s it. But he was involved the whole time. I was just making a suit he would put on, and hoping it fit well.”

Some of the songs in Tutu were later incorporated into Davis’ live show playlist, but the idea of playing the whole album top to bottom only emerged a couple of years ago, as a one-off event, part of a Miles Davis exhibit in Paris.

“I wanted to do a tribute to Miles, but I also knew Miles would absolutely hate the idea of going back in time and recreating something from 25 years ago,” Miller explains. “Miles never liked to look back. ... And then I got the idea: if I could find some young musicians who were babies when Tutu came out and introduce these great young musicians to the world and have them interpret it, now that could be something Miles would appreciate.”

Miller found New Orleans trumpeter Scott, who will be 28 in March; Louis Cato, drums, 25; Federico Gonzalez Pena, piano, 42, and Alex Han, alto sax, 22. The performance was a success, concerts promoters called, and the one-time-only event became a touring show.

“When we first played the music it tripped me out. Every note brought up a memory of when I was hanging with Miles, working on the music, so it was really emotional to play it,” recalls Miller. “But I really enjoyed playing it live, bringing it to life.”

“What you are going to get out of these shows is how much influence this guy had in our music, in all of us,” says Miller. “Because we are all kind of his children, his family. It’s going to be a beautiful thing to see how Miles still lives.”