An Atlanta based, opinionated commentary on jazz. ("If It doesn't swing, it's not jazz", trumpeter Woody Shaw). I have a news Blog @ News . I have a Culture, Politics and Religion Blog @ Opinion . I have a Technology Blog @ Technology. My Domain is @ Armwood.Com. I have a Law Blog @ Law.

Visit My Jazz Links And Other Websites

Atlanta, GA Weather from Weather Underground

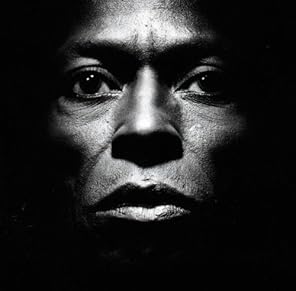

Jackie McLean

John H. Armwood Jazz History Lecture Nashville's Cheekwood Arts Center 1989

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Tuesday, August 09, 2011

Snooky Young: Trumpeter regarded with reverence by his contemporaries - Obituaries, News - The Independent

Any bandleader who had Snooky Young in his band could relax, knowing that he'd filled the most difficult role in the band with the best that there was. Young spent four decades leading the trumpet sections in the bands of Jimmy Lunceford, Count Basie and Lionel Hampton. He was infallible, and earned the respect and affection of all his fellows.

"He was a hell of a trumpet player," said Buck Clayton, who sat beside him in Basie's band. Indeed he was, being unique among lead players in that he was also a splendid jazz soloist. "He's also a gentleman and very pleasant to work with," continued Clayton. "He has a good lip and he's one of the most dependable trumpet players in the business." Lead trumpeters are usually large and muscular men. Young was very small and, on the face of it, delicate. Many's the musician who, sitting next to him for the first time, has almost jumped from his seat at the sudden burst of power from Young's horn.

The laconic Count Basie, who in his autobiography didn't usually describe his sidemen by much more than the dates when they joined and left his band, became comparatively garrulous when Young's name came up. "He's very likeable and wonderful and dependable," said the Count.

Concert audiences don't alwaysrealise how important a good leadtrumpeter is, and consequently names like Conrad Gozzo, the Holy Grail, remained completely unknown to them. But the musicians themselves were aware and, had Young not been such a friendly and unassuming man, his comrades would have regarded him with hushed awe and reverence. As it was, he was just about the perfect jazz musician, whose life was long, happy and entirely distinguished.

Young's first fame came when he stepped out of the section to solo on Lunceford's classic recording of "Uptown Blues" in 1939 when he was 19. "It was different in those days," he said. "They usually had a lead, a growl and a get-off man in the trumpets, but today the lead is thrown about more. I don't think one man could play lead in every number in today's books. So much of what we play is upstairs that it would wear one man down."

The Lunceford band provided he music for the 1941 film melodrama Blues in the Night, which starred Elia Kazan and Jack Carson as musicians. "When Jack Carson jumped up and played a solo it was me playing the music," said Young.

Given the sobriquet "Snooky" by an aunt when he was a small child, Young was known to his musicians by his more obscure nickname, "Sack". Born in Dayton, Ohio, the third of seven children, he began his professional career as a child in the mid-1930ss, playing in his family's band, Young's Snappy Six. His father played saxophone and his mother played banjo and guitar. He and his brother played trumpets and his sister was the pianist. The family toured with a road show called "Brown Skin Models" and it became stranded when the review collapsed in the Deep South. It took the family six months to work its way back to Dayton.

When Louis Armstrong came to Dayton the theatre windows were left open because of the heat, and Young stood in the street and listened to "the most beautiful trumpet I ever heard. There are guys like Charlie Shavers and Clark Terry whose work I'm crazy about, but my main influence was Louis."

Still in school, Young joined the local Wilberforce Collegians, where he met another trumpet player, Gerald Wilson, who was to become a close friend for life. When Wilson joined the Lunceford band he recommended Young to the leader and, over the three years he was with the band, Young took trumpet solos on a dozen or so of the band's records. When the Second World War began the band fell apart as musicians, and went into the services. Young passed his medical to join the US Navy, but was never called up.

"Count Basie came through Dayton at a time when Buck Clayton was sick with his tonsils and he asked if I'd play in the band for a month until Buck was well. I think that was how I made my way with Basie, because he liked my playing. It was like night and day, those two bands," Young said, comparing Basie and Lunceford. "In fact, I had to learn how to play again when I went to the Basie band. Lunceford's was a two-beat band. Basie's was the band that first started to really swing."

Young was to return to work with the pianist for long periods over the next three decades, most prominently from 1957 when he stayed with Basie for five years. Similarly, after firstjoining Lionel Hampton's big band in 1942, he left and rejoined the vibraphone player several times over the ensuing years. In 1943 he dropped off when Hampton reached Los Angeles and joined bands led by Les Hite and Benny Carter.

"It's probably only because he's so valuable in the section," Carter said, "that Snooky hasn't received his due recognition as a soloist."

In 1957 Young became a founder member of the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis big band and also worked for Benny Goodman. Another Basie giant,the tenor saxophonist Frank Foster, who also died recently, pointed the finger in 1958 at last to give Young the prominence he deserved so well. Foster wrote "Who, Me?", a rampaging feature for Young's trumpet. It has all the exultant magnetism of the band at its best, with Young in his solo playing "lead, growl and get-off man" in one magnificent performance. It thrilled crowds in concerts across the US, Europe and Asia. As did his performance of the delicate ballad "Pensive Miss", written as a feature for him with the band by Neal Hefti.

Young came off the road when he left Basie in 1962 and became a studio musician in New York. When The Tonight Show band moved from New York to Los Angeles, he went with it. He stayed with the show from 1972 until 1992. In Los Angeles he enhanced the Basie-inspired Juggernaut, a big band led by Nat Pierce and Frankie Capp, and once again joined his friend Gerald Wilson when Young became the high-note player in Wilson's big band. He was a regular in many of the local jazz groups, notably the Clayton-Hamilton Orchestra and the blues package led by Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham.

"He's one of the most precious human beings I have ever known," said Quincy Jones, topping off the praise for one of the most well-liked jazz musicians of all time.

STEVE VOCE

Eugene Edwards "Snooky" Young, trumpeter: born Dayton, Ohio 3 February 1919; married 1939 (two daughters, one son); died Los Angeles 10 May 2011.

Saturday, June 04, 2011

Ray Bryant, Jazz Pianist, Dies at 79 - NYTimes.com

Cover of Alone at MontreuxRay Bryant, Jazz Pianist, Dies at 79 - NYTimes.com

Cover of Alone at MontreuxRay Bryant, Jazz Pianist, Dies at 79 - NYTimes.comBy NATE CHINEN

Ray Bryant, a jazz pianist whose sensitivity and easy authority made him a busy accompanist and a successful solo artist, beginning in the mid-1950s, died on Thursday. He was 79.

His wife of 20 years, Claude Bryant, said he died at New York Hospital Queens after a long illness. He lived in Jackson Heights, Queens.

Mr. Bryant had a firm touch and an unshakable sense of time, notably in his left hand, which he often used to build a bedrock vamp. Even in a bebop setting, he favored the ringing tonalities of the gospel church. And he was sumptuously at home with the blues, as a style and a sensibility but never as an affectation.

All of this contributed to his accomplishment as a solo pianist. His first solo piano album was “Alone With the Blues,” in 1958, and he went on to make a handful of others, including “Alone at Montreux,” “Solo Flight” and “Montreux ’77.” His most recent release, “In the Back Room,” was yet another solo album, recorded live at Rutgers University and released on the Evening Star label in 2008.

Raphael Homer Bryant was born on Dec. 24, 1931, in Philadelphia, and made his name in that city during its considerable postwar jazz boom. Along with his brother, Tommy, a bassist, he played in the house band at the Blue Note Club in Philadelphia, which had a steady flow of major talent dropping in from New York. (Charlie Parker and Miles Davis were among the musicians they played with there.) In short order Mr. Bryant had plenty of prominent sideman work, both with and without his brother.

One early measure of his ascent was the album “Meet Betty Carter and Ray Bryant,” released on Columbia in 1955. It was a splashy introduction for him as well as for Ms. Carter, the imposingly gifted jazz singer. It was soon followed by “The Ray Bryant Trio” (Prestige), an accomplished album that introduced Mr. Bryant’s composition “Blues Changes,” with its distinctive chord progression.

That song would become a staple of the jazz literature, if less of a proven standard than “Cubano Chant,” the sprightly Afro-Cuban fanfare that Mr. Bryant recorded under his own name and in bands led by the drummers Art Blakey, Art Taylor and Jo Jones.

Mr. Bryant had several hit songs early in his solo career, beginning with “Little Susie,” an original blues that he recorded both for the Signature label and for Columbia. In 1960 he reached No. 30 on the Billboard chart with a novelty song called “The Madison Time,” rushed into production to capitalize on a dance craze. (The song has had a durable afterlife, appearing on the soundtrack to the 1988 movie “Hairspray,” and in the recent Broadway musical production.) He later broke into the Top 100 with a cover of Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe,” released just a few months after the original, in 1967.

But Mr. Bryant’s legacy never rested on his chart success or his nimble response to popular trends. It can be discerned throughout his own discography and in some of his work as a sideman, notably with the singers Carmen McRae and Jimmy Rushing, and on albums like Dizzy Gillespie’s “Sonny Side Up,” on Verve. “After Hours,” a track on that album, begins with Mr. Bryant and his brother playing a textbook slow-drag blues.

Along with his wife, Mr. Bryant is survived by a son, Raphael Bryant Jr.; a daughter, Gina; three grandchildren; and two brothers, Leonard and Lynwood. Mr. Bryant’s sister, Vera Eubanks, is the mother of several prominent jazz musicians: Robin Eubanks, a trombonist; Kevin Eubanks, the guitarist and former bandleader on “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno”; and Duane Eubanks, a trumpeter.

________________________________________

Back during the mid and late seventies Ray Bryant used to play piano regularly at a restaurant around the corner from my apartment on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan called Hanratty's. That restaurant has been gone for many years. Bryant was a funky two fisted pianist who had a winning combination of prodigious technique coupled with a soulful feeling. He will live on through his numerous recordings.

John H. Armwood

Back during the mid and late seventies Ray Bryant used to play piano regularly at a restaurant around the corner from my apartment on 2nd Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan called Hanratty's. That restaurant has been gone for many years. Bryant was a funky two fisted pianist who had a winning combination of prodigious technique coupled with a soulful feeling. He will live on through his numerous recordings.

John H. Armwood

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Roy Hargrove Quintet: Live At The Village Vanguard : NPR

Cover of Roy HargroveRoy Hargrove Quintet: Live At The Village Vanguard : NPR

Cover of Roy HargroveRoy Hargrove Quintet: Live At The Village Vanguard : NPRMay 25, 2011

There's no one standard model of jazz, but there are standards. There's a standard repertoire, for sure; also, standard conventions of instrumentation, group interaction, overall "sound." Trumpeter Roy Hargrove, when he commits to playing straight-ahead jazz, leads a quintet that is very comfortable with those standards. If you're new to jazz, it would seem distantly familiar, like how you might imagine jazz to be. If you aren't new to jazz, you might just find it proves how satisfying those standards remain, and how much room for self-expression is in them.

SET LIST

"The Lamp Is Low" (de Rose/Shefter)

"Hindsight" (Cedar Walton)

"After The Morning" (John Hicks)

"Book's Bossa" (Walter Booker)

"Mr. AT" (Walter Bolden)

"Rouge" (Hargrove)

"Never Let Me Go" (Livingston/Evans)

"Like That" (Hargrove)

"Strasbourg/St. Denis" (Hargrove)

"Bring It On Home To Me" (Sam Cooke)

It's what's made Roy Hargrove a star in the jazz world, and what allows the Roy Hargrove quintet to play two straight weeks at the world-famous Village Vanguard in New York City. WBGO and NPR Music will present a live on-air broadcast and live video webcast of the band's early performance on Wednesday, May 25.

Hargrove's current band is an argument for timelessness; for the idea that the elegance and sophistication of classic post-bebop jazz remains appealing today. On his latest quintet album, 2008's Earfood, it's argued well because Hargrove — aside from being a commanding trumpet player, fast or slow — has focused on writing and picking catchy songs. Not just frameworks for improvisations, but songs: tuneful, simple, grooving songs.

At the Vanguard, he started the set off with a number of tunes by mentors — Cedar Walton, Walter Booker, John Hicks — and standards. (He even took a vocal turn on "Never Let Me Go.") The second half brought more original compositions, including the signature "Strasbourg/St. Denis." Hargrove stood aside one peer, alto saxophonist Justin Robinson, and in front of a younger rhythm section — his working band.

Roy Hargrove is 41 now, decades after his talent was "discovered" at a Dallas, Texas, arts magnet high school by Wynton Marsalis. He became something of a teenage prodigy, touring Europe and Japan before age 17 and playing with jazz legends before he could legally drink. Hargrove's early studio efforts focused on his jazz playing — since then, he's also explored Afro-Cuban music with an ensemble called Crisol and started a funk and soul fusion band called the RH Factor. (He's also been tapped to play behind Erykah Badu, Common and D'Angelo as a sideman.)

But straight-ahead jazz is a core value for Hargrove, the swinging-and-having-fun kind. That sense of tradition, honored gracefully, was on display when his quintet performed at the Village Vanguard — a place he has regularly appeared since the early '90s.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Billy Bang, Jazz Violinist And Vietnam Veteran, Dies At 63 : A Blog Supreme : NPR

Billy Bang, Jazz Violinist And Vietnam Veteran, Dies At 63 : A Blog Supreme : NPR

Billy Bang, a violinist known for intense performances and a wide-ranging sensibility, died Monday night, his agent Jean-Pierre Leduc confirmed. Bang, who had been suffering from lung cancer, was 63.

Born William Walker in 1947, Bang was an important figure on the experimental jazz scene that blossomed in New York in the 1970s. But he gained wider recognition in the last decade for a series of recordings which drew on his military service during the Vietnam War.

His experiences in combat scarred him mentally, and he generally avoided speaking about them until Leduc encouraged him to create what would become 2001's Vietnam: The Aftermath. The album — and its successor, Vietnam: Reflections — received critical acclaim and proved cathartic for Bang.

"There used to be a time where I used to have dreams about it a lot and it's not as often now," he told Howard Mandel for NPR in 2004. "But for a very long time, I suffered a lot in my sleep. But to be honest, I think after I faced the ordeals of what I've gone through — after completing that music, and after rehearsing it, particularly after recording it — I've felt a lot lighter."

Bang grew up in New York City's South Bronx, and actually studied the violin as a teenager. He didn't like it.

"I didn't know what was going on," he told Tom Vitale for NPR in 1993. "I couldn't carry it back on my block. I lived on 117th Street. Can you imagine a little guy carrying a violin, and you talk about guys picking on you, man. I mean, they really did. I had to put the violin down, throw a couple of punches, get thrown at me, go upstairs. I hated to practice it. It sounded terrible."

Despite being offered a scholarship to a boarding preparatory school in New England, Bang never finished high school. He was drafted into the service and, as he told Mandel, he was thrown into combat two days after landing in Vietnam.

As a squad leader, he had to maintain intense focus in combat. There was no music in his life then.

"Only the music of machine guns," Bang told Mandel. "The rhythm of that is what I heard. The only instrument I had was an M-79, M-14 and a .45."

At least initially, the period after his service was hardly any better. In 2005, Bang told Roy Hurst of NPR's News and Notes that returning was a shock.

"When I came home from Vietnam — when I got off the airplane — the next thing I was on was the New York City subway, and that was extremely traumatic for me — I mean, just really destructive to my whole system," Bang said. "I couldn't take the sounds. I couldn't take the people all around. So I finally got home; I didn't want to come outside for a long time, which I didn't do. So my mother was coaxing me to come out and sort of — she was trying to help me to get back to some kind of normality. But I still criticize the United States government for not having a real bona fide re-entry program for veterans."

Bang's trauma led him to heavy drinking and drug use. He joined a Black Liberation group that drew on his wartime experience to help it buy guns. On one trip to a pawn shop, he saw a violin and that led him back to music. After discovering the way that free jazz artists like Leroy Jenkins and Ornette Coleman were using the instrument, he began taking his own study seriously. He moved from the South Bronx to the Lower East Side and immersed himself in the counterculture of likeminded artists.

Bang proved to be an active, passionate performer. Though he was associated with free improvisation, his concepts also came from more traditional jazz and Latin music, and he often incorporated that language into his playing. Tom Vitale's 1993 profile of Bang centered on his project paying tribute to pioneering jazz violinist Stuff Smith.

Dustin Ross/Courtesy of the artist

Billy Bang across the street from his house on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

By the new millennium, Billy Bang had already become a well-respected musician within the jazz world. He spent 10 years with an important group called the String Trio of New York, an improvising ensemble with his violin, guitarist James Emery and bassist John Lindberg.

The Vietnam albums proved to be more high-water marks for his career. Bang called up fellow musicians who had also served in Vietnam for the recording sessions, including conductor Butch Morris.

"It was quite heavy," Morris told Howard Mandel. "I've never seen so many grown men cry. It's not only how he brought this thematic stuff back — it's how he brought the experience back, the experience of being there, the experience of smelling, the experience of seeing, the experience of feeling, the experience of fear, the experience of joy, the experience — he brought back all these experiences. That's what was so frightening in the studio. He brought back the same experience that each of us had."

Billy Bang was scheduled to perform at the Rochester International Jazz Festival in June of this year. Last year, he released a well-received album called Prayer for Peace.

Related articles

- Album review: Billy Bang's 'Prayer for Peace' (avantmusicnews.com)

Friday, April 08, 2011

Randy Weston's African Rhythms Quartet featuring Lewis Nash

Cover of Randy WestonImmersed in African rhythms

Cover of Randy WestonImmersed in African rhythmsBy Geoffrey Himes Friday, April 8, 2011

Most people agree that much of American music — blues, jazz, R&B, hip- hop and gospel — has its roots in Africa, but for many that formula is a vague, sentimental notion, rarely explored and little understood. For pianist Randy Weston, however, that linkage has been the central theme of his music for more than 50 years.

The 85-year-old pianist, who performs at the Kennedy Center on Saturday, has composed jazz suites about Africa, studied African history, collaborated with African musicians, performed across the continent and even lived in Morocco for five years.

“Everybody loves jazz and blues, all these rhythms, and it all comes from Africa,” Weston says. “Africa has always been a mystery, because there’s so little information about what it was like before the people from the north invaded, but you have to know something about Africa to know the human race, because that’s where it started. When I go to Africa, I don’t go as a teacher; I go as a student. I want to find out why I play the way I play.”

Weston is coming to town with a new album, “The Storyteller,” and a new book, “African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston,” co-written by Rockville jazz writer Willard Jenkins. In the book, Weston describes how his fascination with Africa began with an unusual childhood. As a boy in the 1930s, when most Americans’ images of Africa came from Tarzan movies, he was reading books about ancient African kingdoms. His father was a fervent follower of Marcus Garvey, who advocated pride, unity and self-determination for the entire African diaspora.

“The way I was raised made me a much older person,” Weston says on the phone from his home in Brooklyn. “It made me realize that our civilization went back for centuries, that our history didn’t just begin with slavery. I wanted to know how my ancestors could come here in chains to pick cotton and still produce such incredible music. They suffered so much to make it possible for Randy Weston to play the piano, so I have to respect them. To deny them would be to disrespect their efforts.”

By 1960, Weston had recorded 10 albums and established himself as a worthy heir to the jazz-piano tradition of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk. But he hadn’t musically addressed his fascination with Africa. By that decade, however, the civil rights movement in the United States was gathering steam at the same time as the freedom movement in colonial Africa (17 nations would declare their independence that year).

So Weston composed a five-part suite, “Uhuru Afrika” (Swahili for “Freedom Africa”), with help from lyricist Langston Hughes and arranger Melba Liston. They recorded the piece with a 27-member big band that featured Freddie Hubbard, Yusef Lateef, Clark Terry, Kenny Burrell, Max Roach and actor-singer Brock Peters. It was a landmark recording that only whetted Weston’s appetite for further explorations of his African heritage.

Event Information

DETAILS: 7:30pmSaturday, April 9

INFORMATION: 202-467- 4600, 800-

444-1324

PRICE: $30

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts 2700 F St. NW Washington, DC

Location

Like

Terms of Use

He joined a State Department-sponsored tour of Africa in 1961 and another in 1964, and in 1967 moved to Morocco.

“Everywhere I went, I always asked for the most traditional music and the oldest musicians,” Weston recalls. “Jazz is a very young music and America is a very young country, so to gain some perspective you have to go all the way back to where it came from. Like my father and mother, these old musicians have secrets we’ll never fully understand because they lived in a time before us. But we can always learn something from their experiences, so I try to be around the elders as much as possible.”

Willard Jenkins, a frequent contributor to Jazz Times and Downbeat magazines, recognized that Weston had an important story to tell.

“What drew me in Randy’s direction is that I’ve always felt that he’s been underappreciated, perhaps because he was out of the country during a crucial period of his development,” Jenkins says. “He was the only major jazz artist that I know of who actually lived in Africa. It was as if he were on a journey of self-discovery.”

The book is told in Weston’s voice, but it was Jenkins who guided the many interviews over nine years and molded the results into a narrative arc.

“I worked with Willard like I did with Melba [Liston],” Weston says. “He’d turn on the tape recorder, I’d go, ‘Blah, blah, blah,’ and he’d take it away and arrange it. It was the same with Melba; I’d play a piano piece and I’d say, ‘This might be a saxophone solo; this might be for trumpet,’ and she would take it away and arrange it. She had a way of hearing what I did, adding colors and making it sound like me.”

Weston’s album “The Storyteller” was recorded live in 2009 and released late last year. Because it was intended to complement the autobiography, it touches on several scenes from the book. It opens with a solo piano piece titled “Chano Pozo,” the Cuban drummer whose injection of African rhythms into Dizzy Gillespie’s band stimulated Weston’s interest in the roots of jazz. The album revisits such major Weston pieces as “African Sunrise,” “African Cookbook” and Weston’s most recorded composition, “Hi-Fly.” And its title reflects a lesson Weston learned from his time in Africa.

“In Western music,” he says, “to be a master all you have to do is play good — be a great pianist or a great saxophonist — but in Africa, to be a master you also have to be a healer, a naturalist and a storyteller.”

Now that he’s 85, Weston himself is one of those storytelling elders, though he laughingly scoffs at the notion, insisting, “I’m still a baby trying to understand the origin of music, the meaning of music.”

Related articles

Jazz Pianist Cedar Walton Performs at 2010 Calgary Jazz Festival

Jazz Pianist Cedar Walton Performs at 2010 Calgary Jazz Festival

Praised and respected by jazz musicians and audiences around the world, 76-year old jazz pianist Cedar Walton kicks off the 2010 Calgary Jazz Festival. He has collaborated with numerous jazz greats throughout his 25-plus year career, including John Coltrane.

Cedar Walton's Career

Cedar Walton first studied piano with his mother before continuing his education at the University of Denver. His career took off at an after-hours gig at the Denver Club, where he met jazz greats John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Read more at Suite101: Jazz Pianist Cedar Walton Performs at 2010 Calgary Jazz Festival

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Melvin Sparks, Influential Soul-Jazz Guitarist, Dead at 64 - Spinner

Melvin Sparks, Influential Soul-Jazz Guitarist, Dead at 64 - Spinner

Melvin Sparks, an acclaimed jazz-soul session guitarist and fixture in the jam-band scene, died March 13 at his Mount Vernon, N.Y. home, according to the New York Times. The 64-year-old's wife said he had battled diabetes and high blood pressure.

Born in Houston, Sparks grew up around music and got his first guitar at age 11. After working as a teenager in R&B bands -- including a stint in the Upsetters, a group founded by Little Richard -- he moved to New York and became a session player for Blue Note and Prestige.

While working for those two famed labels, Sparks played on records by musicians including Jack McDuff and Chares Earland. In 1970, he released his first of three albums, on Prestige 'Sparks!' In total, he released 10 albums as a leader, with 2005's 'Groove on Up' being his latest. In the '90s and '00s, his playing found new fans on the jam-band scene, thanks to more session work and performances with bands like Galactic, Soulive and Phish's Mike Gordon.

Sparks is survived by his wife, Judy Hassan, four daughters, a son and 13 grandchildren.

Related articles

- R.I.P. Guitarist Melvin Sparks, Bassist Jet Harris (pitchfork.com)

The Shorter, the hotter - Music - IOL | Breaking News | South Africa News | World News | Sport | Business | Entertainment | IOL.co.za

The Shorter, the hotter - Music - IOL | Breaking News | South Africa News | World News | Sport | Business | Entertainment | IOL.co.za

A music interview often begins by referencing musicians the subject has played with. Wayne Shorter, however, is the kind of living legend that other artists reference.

He was born in New Jersey in 1933, and started playing clarinet at 16 before switching to saxophone, going on to win multiple Grammy Awards (six, at last count, with 13 nominations) and earn honorary doctorates from New York University and the Berklee College of Music, among others.

He’s been declared a “jazz master” by America’s National Endowment for the Arts. His many collaborators have included Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Herbie Hancock and Jimmy Smith.

Shorter’s influence on modern music has been likened to that of Picasso on modern art, and Ingmar Bergman’s on contemporary film, and he’s still steaming ahead with quartet and symphonic projects that critics consider to be among the most powerful of his career.

He is as delighted and intrigued by life now as he was as a star-struck teen who climbed a fire-escape at a Norman Granz Philharmonic show to hear Stan Kenton, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and the clarinet-wielding Ilinois Jacquet. Turns out he also boasts a robust sense of humour.

He presents the interviewer with a dilemma, though. What do you ask the man who co-founded Weather Report, the group that became synonymous with the first wave of jazz fusion throughout the 1970s and early 80s, had his orchestra-meets-improvisation work with outfits like the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw described as “having a feel for melody like Puccini (but with) harmonic complexity like Ravel”? Perhaps the best place to start is with a question about what Cape Town audiences can expect to hear from one of modern jazz music’s most prolific composers.

“Actually, we have a challenge,” says Shorter with the slightest of chuckles. “We have to express some music that is a mirror. We have to reflect what’s going on in this planet in total today. To tell a story that talks of courage and of being fearless in the presence of the unknown. It’s the challenge that has always driven me and, in this country (America) at the moment, there is a hesitance to accept this challenge, and to express that musically.

“People try to give a definition of what jazz means, but my definition of jazz is not a fixed one. It’s an evolving definition that grows when it is fuelled by what people are doing and playing. Jazz is an eternal mission that transcends all strategy and all intelligence.

“So many people have been denied so many things in the world,” he continues. “Your country had that, but your country came through, and the music we will be playing will be celebrating that as well.

“The other challenge of what we do is that we communicate without words, but with sound. We try to find something mystical about life; about what is life. We don’t know what life it, but we can try to answer that question without words, and to celebrate it.

“In this country (the US), really creative music is still an alien concept. It’s like that’s the real UFO in the US these days – being creative and moving forward without fear, and with courage. I like what Sonny Rollins said in a documentary. They asked him why did Dizzy and Miles and Charlie play bebop. Sonny looked at them and said: ‘We played bebop to be human.’”

Shorter has sometimes been described as “the Zen philosopher of jazz”, but closer attention reveals that his thoughts are less esoteric than might first be imagined.

“Most audiences have been conditioned to believe that ratings will tell them what to do, and to try to find more of the same of what is being programmed,” he says. “Nobody should be telling you what to do based on record sales and writing hits.

“We have to be original and creative and fearless, and be more; we have to play, and to gather wisdom along the way. The hesitancy to deal with the unexpected – in other words, for things where there is no university or training to deal with them, like improvisation... In today’s world, that is much needed. That’s what I mean by courage.”

At some point in the interview, after Shorter has bent his critical eye and sharp tongue to the music industry and the arts in America, I joke that he’d best hope the CIA isn’t taping the conversation, or they’ll throw him in jail. At the close of the interview, I thank him for his time and generosity of conversation, and bid him farewell.

“Wait, wait, I have something more to tell you,” he says. “You said CIA, but you don’t know what it means. For me, it means that I’m a Coloured Intelligent American, and you all better watch out. The resilience to listen to music that is different, or to go and see off-Broadway theatre rather than what is popular, or read something different... The Madison Square marketing companies will try and stop it, but it’s intrinsic to the spirit of human life. That’s what my CIA is doing.”

We say goodbye and Shorter, the man Max Roach called “The Flash” and who Davis requested as sideman, is still chuckling to himself.

l The Wayne Shorter Quartet plays on Friday and Saturday at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival on the Rosies indoor stage, for which an additional ticket is required after access to the festival proper (Cape Town International Convention Centre; tickets Computicket at 083 915 8000 or Shoprite). Also at the festival are Earth, Wind and Fire, Feya Faku, Esperanza Spalding, The Flames, Youssou N’Dour, Don Laka, Patricia Barber, Hugh Masekela, Jazzanova, Simphiwe Dana, Cindy Blackman and more. On Wednesday there will be a free concert on Greenmarket Square featuring Hanjin, Gang of Instrumentals, the Cape Town Tribute Band, Tortured Soul and Tribe Of Benjamin. See CapeTownJazzFest.com

Sunday, March 20, 2011

‘Jazz - The Smithsonian Anthology,’ Out March 29 - NYTimes.com

Cover of Art Blakey‘Jazz - The Smithsonian Anthology,’ Out March 29 - NYTimes.com

Cover of Art Blakey‘Jazz - The Smithsonian Anthology,’ Out March 29 - NYTimes.comBy BEN RATLIFF

LOOK out: there’s a new jazz canon coming toward you. A boxed set of six discs to be released on March 29, it emanates from the Smithsonian Institution; it is called “Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology.” It surveys jazz chronologically, from its complicated beginnings to its just as complicated near-present.

It was assembled by scholars and critics and broadcasters: serious names. It begins with a solo-piano composition by a Texas-born composer whose father had been a slave (Scott Joplin) and ends with a quartet track led by a Polish trumpeter (Tomasz Stanko) who loves Miles Davis. Text drips from the package, an essay for each of its 111 tracks.

You’re energized, right? Your heartbeat just picked up, your amygdala’s plumping out. You want to know what canons usually address: how and where the anthologizers claim jazz started, how they frame it now. And in the middle, how do they really feel about Coltrane, about late Billie Holiday and Lester Young, about Ahmad Jamal, Miles at the Plugged Nickel, Afro-Latinism, cool and free and fusion, live vs. studio, unsung heroes? More: Is jazz a musical language or a philosophy of action, or is it merely a genre, the art that descends from a body of recorded masterpieces? What’s its relation to race, or sensuality, or geography? And what is the deal with its rhythm sections — why do they sound so incredibly different every 15 years? What keeps the music changing? What makes it tick? What is jazz?

I am both invested in and sick of the subject, having written a kind of jazz-canon book myself, 10 years ago. So, caveat lector. But I ask rhetorically, because I’m still working it out: How could such a righteous cultural product, full of so many sublime parts, feel so cumulatively limp?

My first reaction was that maybe we’ve reached our limit, jazz-canon-wise. In the past one of the primary functions of projects like “Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology” was simply to get this music in print, because in some cases you could not otherwise find it: probably not in your local record store or library, not on the radio, nowhere. Back then there was a causal link between a recording’s availability and the possibility of its influence. Now almost every recording ever made is buyable or poachable online: easy come, easy go, and therefore no music needs protection or special pleading. But that’s nonsense. There is still a need for cultural advocacy, even if the culture is easy to find. Meade Lux Lewis’s ferocious “Honky Tonk Train Blues,” on Disc 1 of this collection, was popular in its time and remains easy to locate online. Still, you’ll most likely never hear it unless someone points you there.

Then I wondered if maybe it’s no longer worth exploring what the new jazz reality — say, New York groups like the trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire’s or the drummer Dafnis Prieto’s, or the New York-Los Angeles band Kneebody — might have in common with King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton. But of course that’s wrong too. The connections are there, the closer you listen: in instrumentation, in the compressed balance between composition and improvisation, in the spirit of revision. And all those new jazz musicians have studied the jazz tradition. They may run far and wide, but they know who their parents are.

But maybe the true problem is that “Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology” isn’t really a canon at all. It’s a House of Representatives. What’s missing is its desire to be any more than a list, rather than an argument or a thesis.

It does not lack for facts, this hundred-dollar toolbox. It is not underinformed. It does more, for instance, with free jazz and Afro-Latin music than some others have done. It represents both popular taste and scholarly consensus. It is balanced in all things, even in its split between popular choices and critics’ favorites. So there’s Miles Davis’s “So What,” Bill Evans’s “Waltz for Debby,” Getz and Gilberto’s “Girl From Ipanema,” Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ “Moanin,’ ” etc. — as well as solid to questionable wild-card choices like the Clark Terry-Bob Brookmeyer Quintet’s “Haig & Haig,” Mary Lou Williams’s “Virgo” and Cab Calloway’s “Hard Times.” Its final disc stops at 2003 — a minor alarm, though I’m resigned to low hopes for the final chapters of these kinds of things. You’ll always disagree about the music of your own time.

The new Smithsonian anthology is fair minded, which is to say strangely anonymous. Though the essays are signed, one can’t be sure whether the signers chose the tracks, and you won’t find out how the anthologizers, individually or as a body, really feel about anything in particular. (The boxed set was created by an executive committee of five — the scholars David Baker, Jose Bowen, John Edward Hasse, Dan Morgenstern and Alyn Shipton — and 42 more on the advisory panel: 47 ! And that’s not including yet a few more writers, who wrote track notes.) It comes with no particular orientation or obsession; it can seem as if there’s little at stake.

It is chronological, which of course carries its own logic, if kind of a dull one. It contains a few inspired sequences, like its tour of the mid-’50s, winding through mostly nonobvious tracks from Chico Hamilton, Lucky Thompson, Sonny Rollins, Sun Ra, Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald with Louis Armstrong. But in general the individual tracks don’t talk to one another much, or linger on an artist and take a stand; and while the boxed set represents styles and eras and trends, it seldom leads you toward deeper questions.

The act of listening to it can also elicit a retrospective sympathy for past canons, on page and disc and screen. For instance Charles Edward Smith’s in “The Jazz Record Book”; Marshall Stearns’s in “The Story of Jazz”; Joachim E. Berendt, Gunther Huesmann and Kevin Whitehead’s, in the second edition of Berendt’s “Jazz Book”; Ken Burns’s, in the television documentary and CD series “Jazz;” Allen Lowe’s “That Devilin’ Tune,” covering jazz up to 1951 in 36 discs and a book; and Gary Giddins’s and Scott Deveaux’s, in their judicious book-length history and CD-ROM project from 2010, also called “Jazz.”

All these had causes to defend or stories to tell: the development of jazz as a self-conscious art form; the centrality of the music’s prehistory; the importance of prescient or outlying musicians to jazz history; the role of jazz in healing America’s race trauma. But what the new anthology might make you miss the most is the object it has been designed to replace: “The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz,” compiled in 1973 and revised in 1987 by the critic Martin Williams.

The American jazz-education movement was just taking shape when Williams’s “Smithsonian Collection” appeared, on six vinyl LPs. (It was eventually transferred to CD; it’s been out of print for a while.) The Williams anthology became standard for jazz-appreciation classes, and on first inspection it appeared only to help you demarcate a big story and save time. Stealthily, it also advanced theories. Williams, who died in 1992, could write as if he didn’t know what fun was. But he listened with great depth and vigor, and his canon had funk in its step.

It favored rhythmic innovation above all else. It had little time for singers. It acknowledged masterpieces, but not reflexively or out of obligation. It bestowed major real estate to a small group of creators — particularly Jelly Roll Morton, Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk and Ornette Coleman — and gave John Coltrane an informed kind of short shrift. If you resented any of his grudges from his writing, you saw them carried over into the anthology. (He found Coltrane tedious and Ahmad Jamal shallow.)

Yet the Williams canon radiated a meta-consciousness of jazz as a creative act. It segued versions of the same song by different people; it knitted together Charlie Christian’s guitar solos from different takes of “Breakfast Feud” with the Benny Goodman Sextet into one long, five-chorus improvisation. And it really engaged with Charlie Parker, presenting pairs of alternate takes of “Embraceable You” and “Crazeology,” cutting them off after Parker’s solo, to demonstrate how true an improviser Parker was. This could seem fanciful or time wasting when telling a big story in a small space; but he picked his spots.

All of that was radical, if not even remix-oriented or bloggy before its time. He seemed to understand implicitly that canon making itself was an act of creativity and revision; that a survey of an art form wasn’t the same thing as a survey of its reception. In any case, Williams’s anthology was argued over because it was worth arguing over.

What I’m saying is: If ever there was a place for style to follow subject, for form to follow function, this is the place. A jazz anthology has got to have spark and tension and originality. In order for jazz to feel like an open subject, we need more challenging suppositions about it, whether they translate as pluralistic or exclusive. But perhaps this just can’t be done by committee. I’ve never heard good jazz from a 47-member band.

Related articles

- Jazz drummer Morello dies at 82 (bbc.co.uk)

- Music Review: Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers - Ugetsu (seattlepi.com)

Monday, March 14, 2011

SFJazz Collective takes on Stevie Wonder: review

Cover of Stefon HarrisSFJazz Collective takes on Stevie Wonder: review

Cover of Stefon HarrisSFJazz Collective takes on Stevie Wonder: reviewIt takes a brave soul to tackle the music of Stevie Wonder. The latest incarnation of the SFJazz Collective happens to contain eight of them.

Having taken on jazz titans like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Thelonious Monk in the past, the group, which played at San Francisco's Herbst Theatre on Friday as part of the SFJazz Spring Season, picked an equally challenging target for its first foray into the pop world.

"We are celebrating the music of one of my great, great heroes," said vibraphonist Stefon Harris. The Grammy-nominated New York musician recalled listening to Wonder's 1976 masterpiece, "Songs in the Key of Life," five times in a row as a kindergartener: "That's when I knew I had a passion for music."

With a blast of horns and a skitter across the vibraphone's bars, intimidation quickly gave way to experimentation at the Herbst. The ensemble features the same lineup for the second year running - Harris, drummer Eric Harland, alto saxophonist Miguel Zenón, bassist Matt Penman, tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, pianist Edward Simon, trumpeter Avishai Cohen and trombonist Robin Eubanks.

Together they offered four distinct, loose-limbed adaptations of some of Wonder's best-known tunes alongside several original compositions by the individual band members.

The voluptuous melody of the Wonder-penned set opener "My Cherie Amour" was pulled apart and served up in an expansive jam that saw Zenón spitting back notes and Harland drawing out a maniacal groove while his head tilted back some 90 degrees.

Penman issued a dark-hued deconstruction of Wonder's "Creepin,' " while Turner retained just a few familiar chord changes amid the rousing fanfare of "Blame It on the Sun." Zenón, meanwhile, a Puerto Rican-born musician who studied at Boston's Berklee College of Music, was responsible for the Caribbean influence on the night's most faithful cover, "Superstition." He said he "put a little rice and beans and plantains into it."

The ensemble's sense of adventure spilled over into the new pieces, which veered from Harris' buoyant tribute to his 2-year-old son, "Lifesigns," to the Israeli-born Cohen's meditative, minimalist encore number, "Family." Brave doesn't really begin to describe it.

The collective serves as the house band for SFJazz, the long-running arts organization that also programs the San Francisco Jazz Festival and Summerfest, along with a host of educational services.

The spring season calendar is highlighted this year by jazz guitarist Marc Ribot, playing a live soundtrack score for Charlie Chaplin's classic 1921 film "The Kid" on Wednesday at YBCA Forum; Randy Newman performing a rare solo concert at Davies Symphony Hall on April 22; and 84-year-old Tony Bennett revisiting some of his biggest hits at the same venue on May 28.

Related articles

- SFJAZZ Collective and Joshua Redman To Perform At 2011 Alaska Airlines/Horizon (theurbanflux.wordpress.com)

- SFJAZZ Announces Spring Season 2011 Lineup (jambase.com)

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Kennedy Center's jazz season could use more variety and experimentation

Cover of Charlie ParkerKennedy Center's jazz season could use more variety and experimentation

Cover of Charlie ParkerKennedy Center's jazz season could use more variety and experimentationBy Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, March 13, 2011

For years, it was reassuring to see Billy Taylor, perhaps the most eminent evangelist jazz has ever known, sitting in the audience or accepting an award on stage at the Kennedy Center. His vision helped get jazz accepted as a central part of our nation's cultural heritage, with an ambitious mix of large-scale festivals and concerts that make the Kennedy Center one of the greatest venues for jazz in the country.

Although Taylor had long since ceded responsibilities for booking and programming to the Kennedy Center's staff, his death in December left a huge inspirational void. During the first full season without Taylor behind the scenes, the center will pay homage to its longtime artistic director for jazz with a celebratory concert and festival Nov. 11 to 26.

The festival, called "Swing, Swing, Swing," will kick off Nov. 11 with Taylor's bassist and drummer, Chip Jackson and Winard Harper, accompanying an all-star lineup of pianists - Geri Allen, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Ramsey Lewis and Danilo Perez - and other musicians.

There will be plenty of vocals during the festival, with Jon Hendricks and Manhattan Transfer appearing together and with George Benson saluting Nat "King" Cole. For participatory fun, the Kennedy Center will open up the grand foyer for swing dancers - complete with dance instructors - and a variety of jazz and swing-oriented groups.

Other jazz highlights of the 2011-12 season include saxophonist Steve Wilson recreating the music of Charlie Parker's remarkable recording with strings (Oct. 7-8); the amazing father-son duo of Dorado and Samson Schmitt performing the gypsy jazz of Django Reinhardt (with Anat Cohen on clarinet) (Oct. 29); singers Tierney Sutton (Dec. 2) and Jane Monheit (Dec. 17); and trumpeter Nicholas Payton (Feb. 10, 2012).

Every year since 1996, the Kennedy Center has presented the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival - an idea Taylor developed. Some wondered at the beginning whether the festival would last beyond one year. Its success has been a testament to Taylor's vision and to the strengthening position of women in jazz. This year's Grammy Award for best new artist didn't go to Justin Bieber, after all - it went to jazz bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding, who will be at the Kennedy Center in May.

It would be nice, however, if the Women in Jazz Festival could look beyond the usual suspects of Dee Dee Bridgewater, Dianne Reeves and Geri Allen, who have appeared multiple times. There are dozens of lesser-known artists across the country who are just as deserving of a national showcase, including such singers as Nancy Marano, Lois Smith, Carol Sloane and Wesla Whitfield, pianists Lynne Arriale and Dena DeRose and trumpeter Ingrid Jensen.

With the international flavor of jazz becoming more pronounced each year, it's time for a Latin jazz festival - one that looks back to Mario Bauza, Machito and Chano Pozo and shows how the music of the Caribbean basin enriched North American jazz.

One of the great successes of Kennedy Center's jazz program has been its KC Jazz Club, a room that features leading musicians in an intimate cabaret setting. But it is open only four months of the year. When other venues are cutting back on jazz, the KC Jazz Club should be a year-round destination, with regular Friday and Saturday performances, plus Sunday matinees for people who don't like to stay out late.

Finally, several of the events next year seem to have inadvertently pointed the way toward a new programming idea that shows real promise. Drummer Roy Haynes, still relentlessly driving the beat at 85, will appear with his Fountain of Youth Band - young musicians in their 20s - on Oct. 14. Alto saxophonist Phil Woods, who turns 80 this year, will perform with his teenage protegee, saxophonist Grace Kelly, on Jan. 27, 2012.

Taylor often mentored younger musicians, including 21-year-old pianist Christian Sands, who will perform at the Nov. 11 concert in Taylor's honor. What better way to celebrate the memory of the man who launched jazz at the Kennedy Center than by inaugurating a series that brings the grand masters of jazz together with their young acolytes who will keep the music alive?

Related articles

- Jazz Great Billy Taylor Dies at 89 (theroot.com)

- Remembering Billy Taylor, Jazz Artist And Educator (npr.org)

- Kennedy Center Announces 2011-12 season (artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com)

Monday, March 07, 2011

Duke Ellington, Before My Time | By Nat Hentoff - WSJ.com

Image via WikipediaDuke Ellington, Before My Time | By Nat Hentoff - WSJ.com

Image via WikipediaDuke Ellington, Before My Time | By Nat Hentoff - WSJ.comI first had the opportunity of being mentored by Duke Ellington in the 1940s when I was part of the Boston jazz scene. In those days I had a radio show that combined music and interviews, and as a part-time reporter for Down Beat, I got to know Duke. Off the air, he once told me: "I don't want listeners to analyze my music. I want them open to it as a whole."

And I was there when he played dances, just to get as close to the bandstand as I could. One night, the band played a number entirely new to me. During one of their quick breaks I whispered to a sideman, baritone saxophonist Harry Carney, "What's the name of that?"

"I don't know," he said. "He just wrote it."

Another sideman, Rex Stewart, who played trumpet and cornet and with whom I used to hang out, told me—and later mentioned in his book, "Jazz Masters of the 30s"—"He snatches ideas out of the air. . . . On the Ellington orchestra's Pullman, he'd suddenly jump as if a bee had stung him . . . and scribble madly for hours—or sometimes only for a minute."

And I learned to come early to performances. While the band would wait for some late- arriving "stars," Duke would often sit at the piano, improvising intriguing stories, sometimes simultaneously starting a new composition.

After I became New York editor of Down Beat in 1953, I talked quite often with Duke, and was instructed not only in music ("Don't listen by category, but to individuals") but also in his deep interest in the history of his people in this land, which became part of his music.

In 1957, I was very surprised and honored when the RCA Records label asked me, with Duke's approval, to select and write the notes for a compilation, later titled "In A Mellotone," of 1940-42 sides—previously unreleased on album—by what was then regarded internationally as his especially nonpareil orchestra. I felt I had been knighted.

Getty Images

'Chord changes? Listen, sweetie.'

Having treasured his music of that period, I knew little of his earlier recordings on other labels until now, with the release of the invaluably illuminating "The Complete 1932-1940 Brunswick, Columbia and Master Recordings of Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra" (Mosaic), produced by Scott Wenzel and Steven Lasker. The latter also wrote the deeply researched and absorbing liner notes that are of permanent value to global listeners, including jazz historians of the Ellington phenomenon.

Mosaic's overall executive director is Michael Cuscuna, who has developed jazz reissues into a high art. He and his team search unremittingly for the original masters and then contact the surviving participating musicians to ensure discographic accuracy. They also take care of all licensing requirements and payments to the musicians' estates. Anything on the Mosaic label is—in jazz parlance—"in the pocket."

As Mr. Lasker notes, when the first recordings in this set were made in February 1932, Duke was nearly 33. He had come to New York from his hometown of Washington nine years before with his five-piece combo, Duke Ellington's Washingtonians. The band continued expanding, reaching eight musicians by 1927. The Ellington impact was being felt strongly at Harlem's Cotton Club. At the same time, he was beginning to be heard nationally on the radio. (Being only 2 at the time, I missed those broadcasts.)

During the summer of 1929, the orchestra appeared in Florenz Ziegfeld's revue "Showgirl." Its performance roused that legendary producer to call the orchestra "the finest exponent of syncopated music in existence. . . . Some of the best exponents of modern music who have heard them during rehearsal almost jumped out of their seats over their extraordinary harmonies and exciting rhythms."

Now, thanks to Mosaic, I have almost jumped out of my seat because the sound engineering by Mr. Lasker and Andreas Meyer brings these Ellington orchestras swinging right into the room. As Billy Strayhorn (eventually Ellington's associate arranger) put it in Down Beat in 1952: "Ellington plays the piano, but his real instrument is the band. Each member of the band is to him a distinctive tone color and set of emotions, which he mixes with others equally distinctive to produce a third thing, which I call the Ellington Effect." That characteristic sound is as present in these recordings as it would later be in the 1940s and beyond.

Long ago, Duke explained to me: "A musician's sound is his soul, his total personality. I hear that sound as I prepare to write, and that's how I am able to write." And he added, smiling, "I know their strengths and weaknesses."

He did have a preference for one section of the orchestra. "Duke loves his brass," sidemen would tell me, and throughout these recordings, you hear how gladdened his brass made him, as he would smile broadly when they drove the ensemble. Also, while his band was his instrument, he was a spurring accompanist on the piano.

With the orchestra as his instrument, this collection is an aural kaleidoscope: tone colors, rhythms and tempos of longing, romance, an exultant life force, urgent love and, of course, what he memorialized in his song, "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got that Swing)."

Among the surprises is the vocalist in "St. Louis Blues" on disc one. At first I couldn't tell who it was. He certainly had lived the blues, fitted right into the band and knew how to scat sing. Then it hit me. It was a young, grooving Bing Crosby.

To younger listeners, two of Duke's vocalists during those years may be new: the vividly magnetic Ivie Anderson, and Adelaide Hall. So is a guest, the largely forgotten Ethel Waters, who moved so deeply into the lyrics that her singing had the power of autobiography. Mosaic should issue a boxed set of her career.

Relatively few sidemen left the orchestra. One who did, Ben Webster, told newcomer tenor-saxophonist Harold Ashby: "Vibe the Governor and Rab [Duke and Johnny Hodges] a little smile from me. Now you'll get your Ph.D. in music because you're with the Boss."

I asked Duke what he looked for when he was screening replacements. "He has to know how to listen," he said.

Trombonist Buster Cooper explained what this meant in my book, "American Music Is.": "I first joined the band in a recording studio. He was writing and said to me: 'Buster, I want you to take eight choruses on this tune.'

"I said, 'Fine, but where's the chord changes?' Duke said, 'Chord changes? Listen, sweetie.'"

Duke was always listening intently to the audience. "At a dance," he said to me, "when [alto saxophonist] Johnny Hodges is telling a love story in a ballad, there's sometimes a sigh from someone in the audience. That sigh becomes part of our music."

In 1966 Duke told interviewer Harvey Cohen ("Duke Ellington's America") why he often assured his audience he loved them madly: "I gets a giggle every now and then, but it's true. I love those people madly. . . . You go up there and they react and you can taste it. . . . Oh, maybe 30 years ago I used to think, 'I play for myself. I express me.' And an artist has to please himself first. But . . . when someone else happens to like what you're doing too, this brings on a state of agreement that is the closest thing there is to sex, because people do not indulge themselves together unless they agree this is the time."

The last time I heard from Duke was in April 1974. He was in the hospital for what turned out to be a fatal illness. Visitors told me that Duke, in bed, was still composing. And that April, I—as did others he knew—received a Christmas card from him.

I was startled but not surprised. He always preferred to look ahead, and in case he wouldn't be around in December, he was bringing seasons's greetings while he could. I was depressed at what I took to be "Goodbye." He died in May.

What came back to me as I looked at that card was what sideman Clark Terry told me: "Duke wants life and music to always be a state of becoming. He doesn't even like definitive song endings to a piece. He'd often ask us to come up with ideas for closings, but when we'd settled on one of them, he'd keep fooling with it. He always likes to make the end of a song sound as if it's going somewhere."

Duke Ellington is, of course, still with us. For many around the world, it's always renewing to open ourselves to his music, as it keeps us going.

Mr. Hentoff writes about jazz for the Journal.

Related articles

- Duke Ellington's Harlemania Orchestra Band (harlemworldblog.wordpress.com)

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Jazz Columns: Todd Barkan: Taking Care of the Music — By Sylvia Levine Leitch — Jazz Articles

Jazz Columns: Todd Barkan: Taking Care of the Music — By Sylvia Levine Leitch — Jazz Articles

Sylvia Levine Leitch interviews longtime jazz producer and presenter Todd Barkan about his life in service of jazz

In this latest interview in my series, "In the Service of Jazz," Todd Barkan—Director of Programming and, literally, the voice of jazz for Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola at Jazz at Lincoln Center, as well as record producer, former club owner and musician—talks about his life in jazz. That life almost came to an abrupt and violent end February 13, 2011, when Todd was involved in a serious car accident driving home to the Bronx on the West Side Highway in New York in his trusty Mercury Sable from a night working with this music he loves. As he recalls from his hospital bed a week later, "An SUV travelling at least 100 miles an hour rear-ended me and propelled my car with such force that it smashed into a tree and landed back onto the highway facing the opposite direction." Todd suffered multiple fractures to his lower leg and to his clavicle, and serious bruises from the force of the air bag. "You know," he shared, "those air bags don't just inflate around you gently. They explode on impact." A kind taxi driver witnessed the accident, called the police, and stayed at the scene to tell what had happened—the SUV took off. And, in an odd twist, Todd's cell phone redialed the last call received before the airbag hit it. So pianist Monte Alexander was treated to a bizarre soundtrack of sirens in the wee hours of Sunday morning, he and his wife thinking it must be one of Todd's latest musical ideas. "They had no idea," Todd chuckled.

Related articles

- Todd Barkan on HammondCast KYOURADIO wishing Todd a Speedy Recovery (hammondjazz.wordpress.com)

Saturday, February 19, 2011

Celebrating Miles Davis - 02/19/2011 | MiamiHerald.com

Cover of TutuCelebrating Miles Davis - 02/19/2011 | MiamiHerald.com

Cover of TutuCelebrating Miles Davis - 02/19/2011 | MiamiHerald.comBy the time of his death in 1991, trumpeter Miles Davis had lived several jazz lives.

Throughout a career spanning 50 years, Davis showed an acute sense for shifting musical paradigms and an uncanny ability to both absorb and transcend the musical trends of the day. Time and again, he reinvented himself as needed, and as he did, he also changed the sound of jazz.

Two sides of Davis’ music — one acoustic, featuring classic songs from albums such as Kind of Blue, the other electric, centering on Tutu, the most memorable studio recording of his late period — are the subject of Celebrating Miles, a concert featuring trumpeter (and Davis’ protégé) Wallace Roney, bassist-producer Marcus Miller, up-and-coming trumpeter Christian Scott and bassist Ron Carter, among others. The show, part of the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Art’s Jazz Roots series, takes place at the Knight Concert Hall at 8 p.m. Friday.

“It’s an honor to be part of a tribute to Miles, although I feel I pay tribute to him every time I play the trumpet,” Roney said in a recent phone interview. “I feel my own music is an extension of what he gave to the art form — but I think everybody’s music has been influenced by him.”

Roney’s career includes stints with Art Blakey, Tony Williams and Ornette Coleman, as well as 16 albums as a leader. He also won a Grammy in 1994 as a member of the Miles Davis Tribute Band, featuring Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Carter and Williams. He will perform in the acoustic half of the concert, leading an exceptional group comprised of Billy Childs on piano, Donald Harrison on alto sax, Javon Jackson on tenor sax, Carter on bass and Al Foster on drums.

Roney’s own music includes distinctly contemporary elements including turntables and down-tempo grooves. But he won’t approach this show like a repertory player performing a role.

“Playing Miles’ music is as much me as playing my own music. Playing Miles’ music is how I grew up, it’s how I’ve learned,” he says. “So it’s me. I don’t have to think ‘Well, now I’m going to role-play.’ All I have to do is go to that part of me.”

Jazz phenom

Roney, who will be 51 in May, was already being hailed as a young jazz phenom when he met Davis at a tribute to the trumpeter at the Bottom Line in New York City in 1983. After hearing him play, Davis took an interest and became his mentor. “He heard himself in me,” says Roney, matter-of-factly. “ ‘You remind me of me,’ he told me. ‘You look at me like I used to look at Dizzy.’ ”

In 1991, Davis invited Roney to be part of his concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. That evening, working with an orchestra conducted by Quincy Jones, Davis revisited some of the charts of his classic collaborations with arranger Gil Evans. Roney was a featured soloist.

He chuckles as he discusses the perception and truth of Davis’ cultivated, forbidding persona.

“Miles had a vibe. He definitely had a vibe. He walked into a room and everybody would turn, and he knew how to use that to make people back away from him,” Roney says. “But he was a beautiful person. He was funny. He was friendly. He was generous. He was everything that people would love in a human being but, if you crossed him, oh buddy, ooooh buddy. Then you’d see the “Evil Miles Davis” — and I saw that, too.”

He says that often lost in Davis’ mystique is the fact that “this man was one of the greatest trumpet players of all time.”

“I got to hear his sound in my ear, and I never heard anybody sound like that in my life,” Roney says. “He had a sound that seemed to come from the clouds. I’m telling you. It was not from this Earth. It came from the clouds.”

For all of Davis’ tough posturing, his sound spoke with a touching vulnerability, which served him well in the ’50s and ’60s (just check his classic ballad playing), but also in the ’70s, as he stirred a witches’ brew of electric rock-jazz fusion.

A new groove

In Tutu, recorded 25 years ago this month, the deep humanity of Davis’ sound is set in a world of synthesizers and pre-programmed grooves. Here, he’s Everyman standing in a shiny, mechanical world of zeros and ones, smooth metal and plastic.

“That’s what I was hoping to get,” said Tutu co-producer Miller, 51, who wrote and arranged most of the songs, and played most of the instruments on the album. “To me it was the sound of someone who had been through so much, trying to make his way in this weird, technological world. Miles’ sound was perfect for that.”

The recording was strictly a studio affair. Co-producer Tommy LiPuma, then the head of jazz at Warner Bros., Davis’ new label, decided not to use a live band. To complement Miller’s work, additional musicians were called as needed. As for Davis’ involvement, Miller recalls that “Miles came in, heard the tracks and told me to call him when I needed the trumpet. That’s it. But he was involved the whole time. I was just making a suit he would put on, and hoping it fit well.”

Some of the songs in Tutu were later incorporated into Davis’ live show playlist, but the idea of playing the whole album top to bottom only emerged a couple of years ago, as a one-off event, part of a Miles Davis exhibit in Paris.

“I wanted to do a tribute to Miles, but I also knew Miles would absolutely hate the idea of going back in time and recreating something from 25 years ago,” Miller explains. “Miles never liked to look back. ... And then I got the idea: if I could find some young musicians who were babies when Tutu came out and introduce these great young musicians to the world and have them interpret it, now that could be something Miles would appreciate.”

Miller found New Orleans trumpeter Scott, who will be 28 in March; Louis Cato, drums, 25; Federico Gonzalez Pena, piano, 42, and Alex Han, alto sax, 22. The performance was a success, concerts promoters called, and the one-time-only event became a touring show.

“When we first played the music it tripped me out. Every note brought up a memory of when I was hanging with Miles, working on the music, so it was really emotional to play it,” recalls Miller. “But I really enjoyed playing it live, bringing it to life.”

“What you are going to get out of these shows is how much influence this guy had in our music, in all of us,” says Miller. “Because we are all kind of his children, his family. It’s going to be a beautiful thing to see how Miles still lives.”

Related articles

- Jazz week: trumpet. Day 4, Miles Davis (whyevolutionistrue.wordpress.com)

- Miles Davis- Perfect Way: the Miles Davis Anthology - review (guardian.co.uk)

- Don Cheadle: Time is right for Miles Davis Biopic (Reuters)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Bea would prepare meals will she sold in expensively. Sometimes I would fall asleep there and Bea would wake me up for the long journey back to Staten Island. This was a special time in my life. The last time I saw Sam play was when Rob Gibson brought Dizzy to Atlanta in 1990 and Sam was in the band.