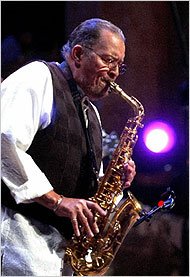

Jackie McLean, Jazz Saxophonist and Mentor, Dies at 74 - New York TimesApril 3, 2006

By PETER KEEPNEWS

Jackie McLean, an acclaimed saxophonist who took a midcareer detour to become a prominent jazz educator, died on Friday at his home in Hartford. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by a spokesman for the University of Hartford, where Mr. McLean had taught since 1970. No cause was given.

Mr. McLean was one of many gifted young musicians who burst onto the New York scene after World War II in the wake of the musical revolution known as bebop. He worked with Bud Powell and Miles Davis before he was out of his teens, and later he gained valuable seasoning in the bands of Art Blakey and Charles Mingus before he began leading his own groups.

Also a prolific composer, Mr. McLean was one of the first alto saxophonists to absorb the pervasive influence of Charlie Parker and shape it into a distinctive personal style. While the influence was clear, especially in his approach to harmony, Mr. McLean's astringent tone and impassioned phrasing marked him as more than just another Parker disciple.

His career had a second act as well. In the late 1960's he put performing aside to concentrate on teaching.

On his arrival at the University of Hartford in 1970, he was a music instructor at the Hartt School. Ten years later he was named director of the university's newly formed African-American music program, one of the first degree programs in the field. In 2000, a year before he received a Jazz Masters grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the university renamed the program the Jackie McLean Institute of Jazz.

For more than two decades he performed and recorded only occasionally. He devoted most of his energy to teaching, both at the university and at the Artists Collective, a community cultural center in Hartford that offered classes in music, theater, dance and the visual arts to local young people, which he founded and ran with his wife, Dollie. She survives him, along with his son Rene, of New York, a saxophonist who frequently performed with him; another son, Vernone, and a daughter, Melonae, both of Hartford; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

In the early 1990's Mr. McLean shifted some of his focus back to performing. "I've always wanted to be remembered for being more than a saxophone player," he told Peter Watrous of The New York Times in 1990, when he returned to New York to perform at the Village Vanguard. "It's been important to put aside my horn and help people, act on what I believe. But the building for Artists Collective will be going up in the next two years, and the music department is now a full-degree program, so it's time to get back to playing."

John Lenwood McLean was born in Harlem on May 17, 1931. (Many sources give his year of birth as 1932, but The Grove Dictionary of Jazz and other authoritative reference works say he was born a year earlier.) The son of a jazz guitarist, he began studying saxophone at 14, starting on soprano but switching to alto after a few months.

Bud Powell, a neighbor who was the leading pianist of the bebop movement and a neighbor, took Mr. McLean under his wing. He also worked with the tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins, another neighbor, and soon caught the attention of Miles Davis, who was just beginning his career as a bandleader. Davis used both Mr. McLean and Mr. Rollins as sidemen on one of his first recordings, in 1951.

Mr. McLean began recording his own albums in 1955. He also had a brief but memorable stage and screen career, appearing in the 1959 Off Broadway production of "The Connection," Jack Gelber's play about drug addiction, and in the 1961 film version, directed by Shirley Clarke.

Mr. McLean was in a sense playing himself. His character was a member of a jazz combo, which provided the music as well as taking part in the action. His character was also a heroin addict — as, he later acknowledged, was Mr. McLean himself. He eventually kicked the habit, and when he became a teacher he often spoke to his students about the dangers of drugs.

In his younger days Mr. McLean was identified with the aggressive, rhythmically charged offshoot of bebop known as hard bop. But in the early and middle 1960's he surprised his listeners (and alienated some critics) by embracing the avant-garde movement then known simply as "the new thing" and later called free jazz, on a series of daring albums for Blue Note with names like "Destination Out" and "One Step Beyond." He even enlisted Ornette Coleman, one of the fathers of the new music, as a sideman on "New and Old Gospel." Although Mr. Coleman's main instrument, like Mr. McLean's, was alto sax, he played trumpet on that album.

But Mr. McLean preferred not to talk about his music in terms of categories. "I've grown out of being just a bebop saxophone player, or being a free saxophone player," he told Jon Pareles of The Times in 1983. "I don't know where I am now. I guess I'm somewhere mixed up between all the saxophonists who ever played."

No comments:

Post a Comment